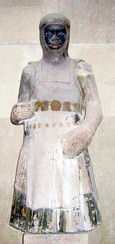

Act concerning 'Egyptians', 1530 HLRO HL/PO/PU/1/1530/22H8n9. Click on image for transcription.

Act concerning 'Egyptians', 1530 HLRO HL/PO/PU/1/1530/22H8n9. Click on image for transcription. It was a very short discussion (for a longer one, see this interview with Vox Africa TV; for more detail on the status of Africans in Tudor England, see my articles on "Slavery and English Common Law"; on "Why Slavery shouldn't distort the History of Black People in Britain" and the case of Caspar van Senden and his failed attempts to transport Africans from Britain in 1596-1601).

However I was puzzled by Onyeka's reference to an African in Tudor Blackburn, so I looked it up in his book and found (on p.361) a reference to the baptism of "Leticia" whose father is described as "Willm Voclentine Egiptian", on 3rd December 1602 in the record of St. Mary's, Blackburn, now held at the Lancashire Record Office.

Other similar examples I found in my research include ‘Anthoine an Egyptian’, buried in Gravesend on 26 May 1553, and ‘Batholomew the sonne of an Egiptian’ baptized in Barnstaple on 23 August 1568.

However, I didn't include these references in my thesis because I didn't feel that they could be taken as straightforward evidence of individuals who came from Egypt.

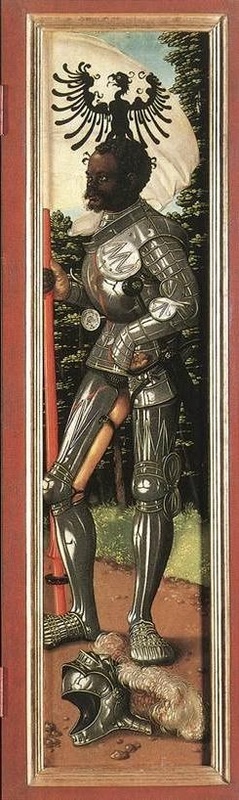

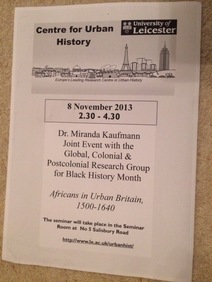

The people referred to as "Egyptians" at this time were ‘gypsies’, or Roma/Romany people, of Hindu origin. Both linguistic and genetic studies have confirmed their origin in the Indian subcontinent. A Parliamentary Act of 1530 concerning Egyptians (illustrated above, and transcribed here) explained that:

"before this tyme divers and many owtlandisshe people calling themselfes Egiptsions using no craft nor faict of merchandise, have comen in to thys realme and goon from Shyre to Shyre and place to place in grete companye and used grete subtile and craftye meanys to deceyve the people bearing them in hande that they by palmestrye could tell menne and Womens Fortunes and soo many Tymes by craft and subtiltie hath deceyved the people of theyr Money & alsoo have comitted many haynous Felonyes and Robberyes to the grete hurt and Disceipt of the people that they have comyn among."

Further Acts concerning ‘Egyptians’ were passed in 1552, 1554, and 1562. They were to be banished, their goods forfeited. By 1562, this was somewhat modified by the ruling that those born in England were to be placed in service.

The fact that these people did not come from Egypt was recognised by at least one contemporary writer. Thomas Dekker wrote in Lantern and Candlelight (1608):

"If they be Egyptians, sure I am they never descended from the tribes of any of those people that came out of Egypt. Ptolemy, King of the Egyptians, I warrant never called them his subjects; no nor Pharoah before him."

For more on Egyptians in Early Modern England, have a look at Chapter 3 of D. Mayall, Gypsy Identities, 1500-2000: From Egipcyans and Moon-men to the Ethnic Romany (2004).

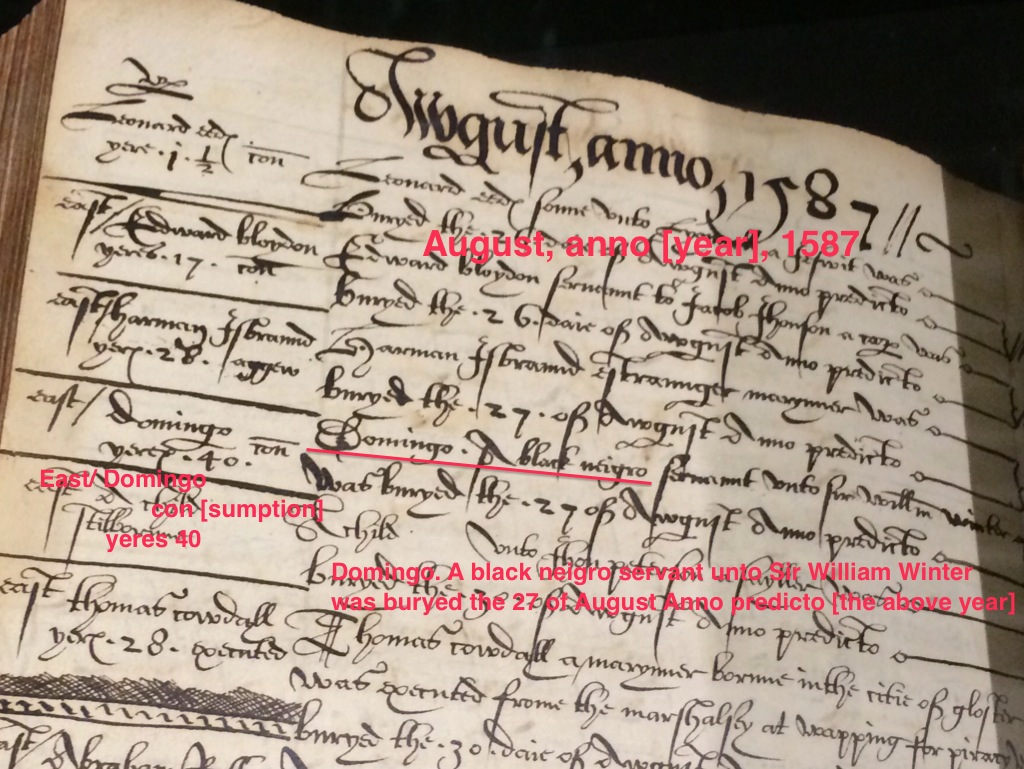

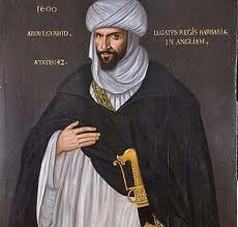

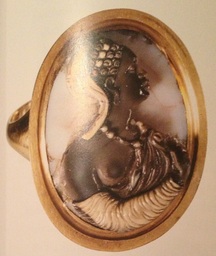

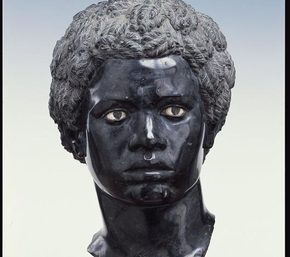

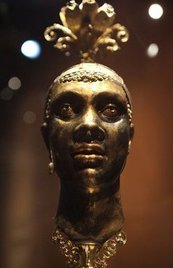

When an individual really is of African origin, the records are not slow to report or comment on it. It is only when an individual is described as ‘a/the blackamore’, ‘a/the negro’, or we are told where they come from or were born that we can be completely sure of their identities.

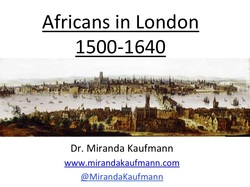

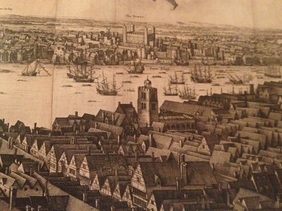

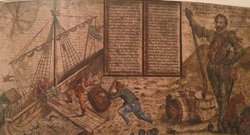

There is enough certain evidence of Africans in Tudor England (for example, this list of references found in London parishes, one of which is pictured below; my own research gathered evidence of over 360 Africans in Britain, 1500-1640, some 200 of which date from the Tudor period) to work with, without having to include these misleadingly-named "Egyptians".

RSS Feed

RSS Feed