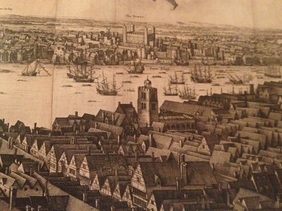

Detail from Hollar's London showing St. Olave's

Detail from Hollar's London showing St. Olave's One of the first things you see when you enter the exhibition is this amazing map of London, created by Wenceslaus Hollar in 1647 (so technically a while after Shakespeare died). It shows the Globe, and also lots of churches, such as St. Olave Tooley Street, shown here across the Thames from the Tower. St. Olave's was the parish where Reasonable Blackman, a silkweaver, and his family lived in the 1590s and ‘Constantyn a negare’ was buried on 5 November 1605. Many of the other churches marked on the map have similar entries in their parish registers...

Iznik Turkish ceramic ewer, British Museum.

Iznik Turkish ceramic ewer, British Museum. This Iznik Turkish ceramic ewer, made in London in 1597-8, may have been made for Paul Bayning, a prominent Levant merchant. What is not revealed in the exhibition is that Baning was also a huge sponsor of privateering voyages and had at least five Africans in his household. In 1593 ‘three maids, blackamores’, are recorded as lodging in his house. In March 1602 ‘Julyane A blackamore servant Wyth Mr Alldermanne Bannying of the age of 22 yeares’ was christened at St. Mary Bothaw. In 1609, ‘Abell a Blackamor’ appeared before the Governors of the Bridewell, ‘his M[aste]r Paul Bannyinge present’, and Bayning’s 1616 will made provision for the education of ‘Anthony my negro’.

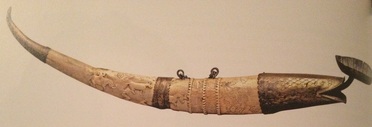

African horn, British Museum

African horn, British Museum This horn was carved in the Calabar region (modern Nigeria) in the 1500s, then found its way to England, where in 1599 it was recarved as a drinking cup, and inscribed:

"Drinke you this and thinke no scorne

Although the cup be much like a horn."

It was later further adapted to be an oil lamp. This strange object has travelled a long way, through many incarnations. It demonstrates the existence of trading links with Africa in Shakespeare's time, which were increasingly regular from the 1550s. Richard Hakluyt chronicled many of these early voyages in his Principall Navigations.

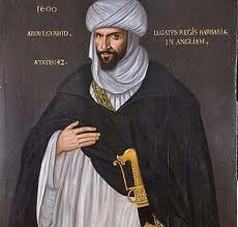

c.1600, University of Birmingham

c.1600, University of Birmingham Abd-al-Wahid bin Masoud bin Muhammad al-Annuri, portrayed here, led an embassy to the court of the 'sultana Isabel' (Elizabeth I) in 1600, but was in fact only one of a series of such ambassadors. Moroccan envoys also visited London in 1551 and 1589. The shared enemy was Spain, but the proposed alliance never amounted to much. A clue to the problems can be found in the letter John Chamberlain wrote to Dudley Carleton on 15 October 1600:

"The Barbarians take theyre leave sometime this week, to goe homeward for our merchants nor mariners will not carry them into Turkie, because they thinck it is a matter odious and scandalous to the world to be friendlie or familiar with Infidells but yet yt is no small honour to us that nations so far removed and every way different shold meet here to admire the glory and magnificence of our Queen of Saba [Sheba]."

Detail from Sir Henry Unton, c.1596, National Portrait Gallery

Detail from Sir Henry Unton, c.1596, National Portrait Gallery The unusual biographical portrait of Sir Henry Unton, painted posthumously for his widow c.1596 shows this masque of Mercury and Diana being performed at his wedding in 1572. The procession behind these main characters consists of small, childlike black and white figures, which have been identified as Cupids. The black figures are of interest as they are a rare visual depiction of the trend for "counterfeit blackamoors" in pageantry and masques. For example, in 1566, on the occasion of the baptism of the future James VI and I, six shillings was laid out from the royal coffers for: ‘thre lamis skynnis quhairof was maid four bonnets of fals hair to the saidis mores’- so four Scots wore lamb's wool wigs to imitate African hair as part of their costumes. Why were these "Masques of Moors" so popular in the sixteenth century?

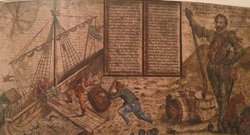

German broadside, late 1580s, British Library

German broadside, late 1580s, British Library This German broadside from the late 1580s celebrates Drake as a Protestant hero, freedom-fighter and scourge of the Catholic Spanish.

The catalogue speaks of his circumnavigation and raids on the Spanish Caribbean, but doesn't mention his many encounters with Africans on those voyages (which I blogged about here) or the fact that some of them returned to England with him.

Recollection of Titus Andronicus, Henry Peacham, c.1594, Longleat Hose, Wiltshire

Recollection of Titus Andronicus, Henry Peacham, c.1594, Longleat Hose, Wiltshire This drawing, c. 1594 by Henry Peacham illustrates Titus Andronicus. It shows that the character of Aaron, described as a 'moor' is certainly thought of as black, not merely 'tawny'. The actor is most likely an Englishman, in costume. A good book on this (which in fact uses this image on its cover) is V.M. Vaughan's Performing Blackness on English Stages.

Playing card, 1644

Playing card, 1644 Cleopatra was of course an African Queen, though some people seem to forget Egypt is in Africa, a complaint I've heard from Tony Walker, who shows people Cleopatra's Needle on the Embankment on his Black History Walks. Shakespeare at least imagined Cleopatra as having dark skin. He describes her as having a ‘tawny front’ (Antony and Cleopatra, I. i. 4-6) and being 'with Phoebus’ amorous pinches black' (I. v. 29). This identity is not always clear in the various images of the Egyptian queen in the British Museum's collection. The artists seem to have been more interested in portraying her death by snake venom- most including an asp biting her bared bosom. My favourite was the set of French playing cards (shown left): Le Jeu des Reynes Renommées (The Game of Famous Queens) by Stephano della Bella (1644). The gift shop really missed a trick by not stocking a replica pack!

c. 1525-30, Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

c. 1525-30, Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam This amazing portrait was painted by Jan Jansz. Mostaert c. 1525-30. He worked at the court of Margaret of Austria, regent of the Netherlands, in Mechelen, near Antwerp. Unfortunately, we know very little about the man in this painting. We don't even know his name. But he has all the trappings of a high-ranking courtier. Of special significance is the badge in his hat, which has been identified as a badge given to pilgrims who had visited the Madonna of Hal, a shrine associated with the Valois and Hapsburgs. The British Museum has one in its collection (below, right). This sends a clear message that this man, like Othello (II, iii, 307) and at least 67 Africans in Britain, 1500-1640, was a baptised Christian. Curiously, the Madonna of Hal (below, left) is a Black Madonna, an ambiguous symbol, but one that seems strangely appropriate here!

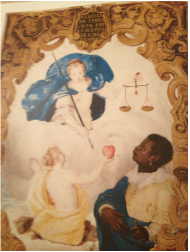

Venetian Commission, 1587, British Library

Venetian Commission, 1587, British Library This illustration of a commission granted to Tommaso Morosini dalla Sbarra (1546-1622), a Venetian patrician, is sadly not a portrait, but part of an allegory of Truth and Justice that has yet to be fully explained. It's suggested that the black figure wearing the family's heraldic colours of gold and blue may be a pun on the 'Moro' (Moor in Italian) of 'Morosini'. So in some ways, this is a more artistic development of the Moor's heads found on heraldic coats of arms across Europe, and even in the arms of the current Pope, Benedict XVI.

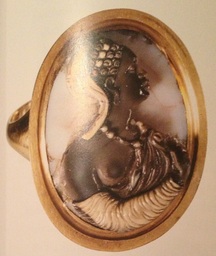

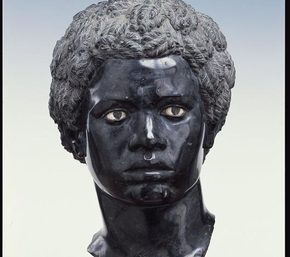

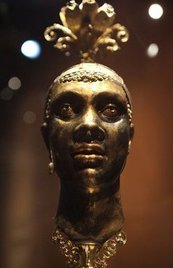

Cameo, N.Italy or Prague, c. 1600, British Museum

Cameo, N.Italy or Prague, c. 1600, British Museum Black Africans appeared in decorative works of art, from cameos, like this one showing an African woman, made c.1600 in Prague or North Italy (now set in a modern gold ring), to sculptures, such as this marble, classically-inspired bust made by Nicholas Cordier in Rome (below, left), and even the splendid gilt-silver cup made by leading Nuremberg goldsmith,Christoph Jamnitzer in about 1602 (below, right). This cup may in fact have been a sports trophy at a Saxon court tournament to celebrate Christian II's wedding to Hedvig of Denmark, which makes me think of the Tournament of the Black Lady held at the court of James IV of Scotland a hundred years before, described in William Dunbar's poem, Ane Blak Moir.

Skyphos, Boeotia, Greece, 450-420 BC, British Museum

Skyphos, Boeotia, Greece, 450-420 BC, British Museum Shakespeare's ‘damned witch Sycorax’, mother to Caliban in Shakespeare’s The Tempest (1610-11), was a native of Algiers. Her name may have been inspired by Circe, the witch who turned Odysseus's men into swine on her Greek island.

Interestingly, this Greek pot shows Circe as a black African woman. In the Tempest, Sycorax is said to have been:

'hither [to the island] brought with child,

And here was left by th’sailors.’ (I. ii. 318-20)

Her fate is not entirely fictional. On his circumnavigation voyage of 1577-80, Drake abandoned a heavily pregnant African woman on Crab Island, Indonesia, an action for which he 'purchased much blame' at the time, but not in later legend.

A Daughter of Niger, Inigo Jones, 1605, Chatsworth

A Daughter of Niger, Inigo Jones, 1605, Chatsworth On 6 January (Twelfth Night) 1605, Ben Jonson's Masque of Blacknesse was performed at the Old Banqueting House before the court of James I and Anne of Denmark. This sketch by architect and scenery-builder extraordinaire Inigo Jones shows the costume of one of the masquers, to be dressed as a 'Daughter of Niger'. This performance and its sequel, the Masque of Beauty (1606), in which the Queen and her ladies themselves blacked up to play the daughters of Niger, who seek beauty and become white thanks to the rays of the British sun (which represented King James) were perhaps the most sophisticated expression of an ongoing interest in 'Masques of Moors' (see no.5, above).

"I speak of Africa and golden joys" (Henry IV, Part 2: V, iii, 101)

RSS Feed

RSS Feed