Book Reviews

I've been reviewing history books, mostly for the TLS (Times Literary Supplement) and BASA (Black and Asian Studies Association) Newsletter, since 2007. Most of my articles are related to my research into 'Africans in Britain, 1500-1640', or the Tudor and Stuart period. Last year, I made the front cover of the TLS with my review of The Image of the Black in Western Art. Of all the books reviewed here, the one I probably enjoyed reading the most was John Guy's A Daughter's Love: Thomas and Margaret More.

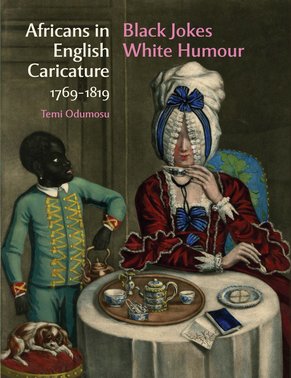

Temi Odumosu, BLACK JOKES, WHITE HUMOUR: AFRICANS IN ENGLISH CARICATURE, 1769–1819, Slavery & Abolition journal, Published online: 15 Nov 2018

In Boney’s Inquisition: Another Specimen of his Humanity on the Person of Madame Toussaint, a hand-coloured etching published in London on 25 October 1804, Charles Williams draws Napoleon looking on as four of his henchmen squeeze the naked nipples of Suzanne Simone Baptiste L’Ouverture with red-hot pincers and pull off her fingernails with a pair of tongs. This gruesome image led Temi Odumosu to discover a letter published in the national paper Bell’s Weekly Messenger four days before the print. Penned by a Madame Bernard, widow of a Saint-Domingue planter now resident in New York, it detailed the gruesome torture the wife of the famous Haitian revolutionary had been subjected to before she managed to escape to America. After sessions in Bordeaux and Paris, Bernard relates that Suzanne had endured ‘the most excruciating pain’ and sustained no less than 44 wounds to her body. She lost the use of her left arm and ‘pieces of flesh have been torn from her breasts as if with hot irons, together with six nails off her toes.’ Worst of all, she suffered a miscarriage. Historians had previously assumed that ‘Madame Toussaint’ died in a French prison: this print, like so many others in this eye-opening book, opens a ‘fascinating window into history’, allowing us to see the past anew.

For this beautifully illustrated study of African figures in English caricature, Odumosu has painstakingly unearthed over 600 prints created during the 50-year period in which this art form was at its height. Many were previously unknown, unpublished, or even suppressed. The more familiar works, including examples by major satirists such as Gillray, Rowlandson, and both Cruikshanks, have rarely, if ever, been considered in this context. more

For this beautifully illustrated study of African figures in English caricature, Odumosu has painstakingly unearthed over 600 prints created during the 50-year period in which this art form was at its height. Many were previously unknown, unpublished, or even suppressed. The more familiar works, including examples by major satirists such as Gillray, Rowlandson, and both Cruikshanks, have rarely, if ever, been considered in this context. more

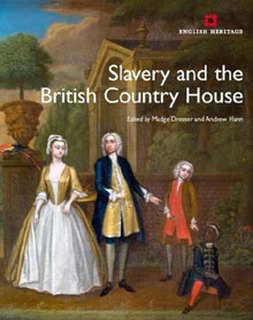

What are they hiding in the dungeon? SLAVERY AND THE BRITISH COUNTRY HOUSE, ed. M.Dresser and A.Hann, Review, TLS, 18 October 2013, p.30.

“Did not you hear me ask him about the slave–trade last night?”

“I did—and was in hopes the question would be followed up by others. It would have pleased your uncle to be inquired of farther.”

“And I longed to do it—but there was such a dead silence!”

- Jane Austen, Mansfield Park, Chapter 21.

Inspired by this passage, Madge Dresser and Andrew Hann use the term ‘Mansfield Park complex’ to describe a similar reticence in the heritage industry. In the novel, Fanny’s uncle, Sir Thomas Bertram is both the owner of Mansfield Park and the absentee proprietor of a sugar plantation in Antigua. In the first essay of this new collection, Nicholas Draper shows that 44 British country houses have similar links to Antigua. Overall, Slavery and the British Country House refers to over 150 British properties with links to slavery.

The genesis of this volume can be traced back to the surge of research prompted by the bicentenary of the abolition of the slave trade in 2007, via a conference hosted by English Heritage, the University of the West of England and the National Trust in 2009. Whether surveying areas near slave ports such as Bristol and Liverpool; connections with colonies such as Antigua or St.Vincent; or focusing on particular houses such as Brodsworth Hall in Yorkshire or Normanton Hall in Rutland, these studies both break the silence and provoke further questions. more

“I did—and was in hopes the question would be followed up by others. It would have pleased your uncle to be inquired of farther.”

“And I longed to do it—but there was such a dead silence!”

- Jane Austen, Mansfield Park, Chapter 21.

Inspired by this passage, Madge Dresser and Andrew Hann use the term ‘Mansfield Park complex’ to describe a similar reticence in the heritage industry. In the novel, Fanny’s uncle, Sir Thomas Bertram is both the owner of Mansfield Park and the absentee proprietor of a sugar plantation in Antigua. In the first essay of this new collection, Nicholas Draper shows that 44 British country houses have similar links to Antigua. Overall, Slavery and the British Country House refers to over 150 British properties with links to slavery.

The genesis of this volume can be traced back to the surge of research prompted by the bicentenary of the abolition of the slave trade in 2007, via a conference hosted by English Heritage, the University of the West of England and the National Trust in 2009. Whether surveying areas near slave ports such as Bristol and Liverpool; connections with colonies such as Antigua or St.Vincent; or focusing on particular houses such as Brodsworth Hall in Yorkshire or Normanton Hall in Rutland, these studies both break the silence and provoke further questions. more

Judith Curthoys, THE CARDINAL’S COLLEGE: CHRIST CHURCH, CHAPTER AND VERSE, TLS, 22 June 2012, p.27.

Every October, Christ Church issues matriculants with a brief history of their new home. Written by Hugh Trevor-Roper in 1950, it tells how Cardinal Wolsey’s 1525 foundation (confiscated by Henry VIII, like Hampton Court, and re-founded in 1546) went on to produce thirteen Prime Ministers, eleven Viceroys of India, and others including William Camden, John Locke, John Ruskin and Lewis Carroll.

Judith Curthoys’s book is, however, the first full-length history of ‘the House’. Many popular myths are dispelled here: there is no evidence that the Master’s Garden was won in a poker game or that members were allowed to kill swans (though there was an annual swan census). New stories take their place: from the foul death of Francis Bayly, who drowned in the Peckwater privy in 1713, to the Bullingdon Club members who smashed all the windows in Peckwater Quad after a dinner in 1892, to W. H. Auden’s gift of a refrigerator to the Senior Common Room in the 1950s, to ensure that his martinis were served at the correct temperature.

As college archivist, Curthoys displays an unrivalled familiarity with the records, but sometimes seems reluctant to interrogate her sources too deeply or tarnish the reputation of her subject. There is no counterbalance to Canon Stratford’s character assassination of Dean Atterbury (1711-13) or any attempt to investigate from which ‘well-known bank’ John Bull (treasurer 1832-1857) withdrew the college’s money when he saved it from ruin. Nor does she question whether it was merely coincidence that Henry Chadwick resigned the deanery the year before women were admitted in 1980.

Curthoys's sound intention to avoid writing a ‘mini-Dictionary of National Biography’ has resulted in regrettably brief references to some of the college’s best-known figures. Trevor-Roper, for instance, is described as ‘researching the truth behind the death of Hitler’ with no mention of his later authentication of the forged Hitler Diaries.

Curthoys has written a history of the institution, its Dean, its Canons, and its Students (Fellows), in which undergraduates are rarely glimpsed. Then, perhaps as now, they were just passing through, only making their mark on the archives when they broke the rules.

Judith Curthoys’s book is, however, the first full-length history of ‘the House’. Many popular myths are dispelled here: there is no evidence that the Master’s Garden was won in a poker game or that members were allowed to kill swans (though there was an annual swan census). New stories take their place: from the foul death of Francis Bayly, who drowned in the Peckwater privy in 1713, to the Bullingdon Club members who smashed all the windows in Peckwater Quad after a dinner in 1892, to W. H. Auden’s gift of a refrigerator to the Senior Common Room in the 1950s, to ensure that his martinis were served at the correct temperature.

As college archivist, Curthoys displays an unrivalled familiarity with the records, but sometimes seems reluctant to interrogate her sources too deeply or tarnish the reputation of her subject. There is no counterbalance to Canon Stratford’s character assassination of Dean Atterbury (1711-13) or any attempt to investigate from which ‘well-known bank’ John Bull (treasurer 1832-1857) withdrew the college’s money when he saved it from ruin. Nor does she question whether it was merely coincidence that Henry Chadwick resigned the deanery the year before women were admitted in 1980.

Curthoys's sound intention to avoid writing a ‘mini-Dictionary of National Biography’ has resulted in regrettably brief references to some of the college’s best-known figures. Trevor-Roper, for instance, is described as ‘researching the truth behind the death of Hitler’ with no mention of his later authentication of the forged Hitler Diaries.

Curthoys has written a history of the institution, its Dean, its Canons, and its Students (Fellows), in which undergraduates are rarely glimpsed. Then, perhaps as now, they were just passing through, only making their mark on the archives when they broke the rules.

A subtle bulwark of canvas: 'THE IMAGE OF THE BLACK IN WESTERN ART, VOLS. I-III, ed. David Bindman, Henry Louis Gates et. al.’ Review, TLS, 23 March 2012, pp. 8-9.

The editors of these monumental and groundbreaking volumes have been through a “journey of exhilaration and pain” to bring these beautifully reproduced and thought-provoking images to our attention. The project began in 1960 when the French-Texan art collectors John and Dominique de Menil commissioned the research that resulted in a photographic catalogue containing over 30,000 images, which now survive in duplicate at the W. E. B. Du Bois Institute for African and African American Research at Harvard and the Warburg Institute in London.

Although the first two volumes, covering the Ancient and Medieval periods, were published in 1976 and 1979 and were followed by Volume Four, From The American Revolution to World War I, in 1989, the projected third volume, discussing the intervening period, which saw the rise and fall of the transatlantic slave trade, never emerged, and publishing was discontinued after the death of Dominique de Menil in 1997. Now, with $3.6 million having been raised to endow the archive at Harvard, the series is being reissued under the aegis of David Bindman and Henry Louis Gates, Jr, and the third volume, From the “Age of Discovery” to the Age of Abolition, has been published for the first time, in three parts (“Artists of the Renaissance and Baroque”, “Europe and the World Beyond” and “The Eighteenth Century”). more

Although the first two volumes, covering the Ancient and Medieval periods, were published in 1976 and 1979 and were followed by Volume Four, From The American Revolution to World War I, in 1989, the projected third volume, discussing the intervening period, which saw the rise and fall of the transatlantic slave trade, never emerged, and publishing was discontinued after the death of Dominique de Menil in 1997. Now, with $3.6 million having been raised to endow the archive at Harvard, the series is being reissued under the aegis of David Bindman and Henry Louis Gates, Jr, and the third volume, From the “Age of Discovery” to the Age of Abolition, has been published for the first time, in three parts (“Artists of the Renaissance and Baroque”, “Europe and the World Beyond” and “The Eighteenth Century”). more

‘THE IMAGE OF THE BLACK IN WESTERN ART, VOLS. I-III, ed. David Bindman, Henry Louis Gates et. al.’ Review, Black and Asian Studies Association Newsletter, 62, March 2012, p. 29.

They say a picture is worth a thousand words. These pictures come with thousands of scholarly words, but it is their visual impact that demonstrates most forcefully that black people have been present in western culture from Ancient Egypt, Rome and Greece, all the way through to “The Age of Obama” and that they have been portrayed in a myriad of different ways by western artists. The ‘Images of the Black’ in these volumes

range from statues of black saints such as St. Maurice, to portraits of notable African ambassadors and kings, poets and musicians, or drawings of literary characters.

The series (first published 1976-1989) is being reissued, with an entirely new third volume, the ‘Age of Discovery to the Age of Abolition’, in three parts covering Artists of the Renaissance and Baroque, Europe and the World Beyond and The Eighteenth Century. more

range from statues of black saints such as St. Maurice, to portraits of notable African ambassadors and kings, poets and musicians, or drawings of literary characters.

The series (first published 1976-1989) is being reissued, with an entirely new third volume, the ‘Age of Discovery to the Age of Abolition’, in three parts covering Artists of the Renaissance and Baroque, Europe and the World Beyond and The Eighteenth Century. more

‘Peter Fryer, Staying Power’, Review, Black and Asian Studies Association Newsletter, 59 (March 2011), pp. 36-7.

Fryer’s masterly synthesis is still an impressive read 26 years after it was originally published. It has become a classic, a standard reference text. Although much research has been made recently into the areas he covers, no one has as yet made the labour of love necessary to bring it all together again in one narrative sweep. Fryer takes us through the history of the black presence in Britain from the Romans to the Brixton riots. His journalistic background shines through in his easy narrative style, and masterful handling of a myriad of facts. However, the narrative imperative does obscure much analysis, or argument more complicated that ‘we woz ‘ere’. That said, some facts speak for themselves, such as the account of the colonial planter who muzzled his cook to prevent her from eating his food as she prepared it or Learie Constantine, the famous Trinidadian cricketer being barred from a London hotel in 1943. There is an overly broad definition of the term ‘black’. Fryer unquestioningly takes on the perspective of the racialists- that all non-whites are ‘black’, and so tries to bring together the very different stories of Asian and African immigration, whilst devoting far more space to the African.

It was in fact his role as a journalist that first piqued his interest in the subject, when he was sent to cover the arrival of the Empire Windrush in 1948. His book ably demonstrates the ignorance of those who believed this was the first arrival of blacks in Britain, and who called for them to go back to where they came from. In fact he shows that there were black people in Britain before the Anglo-Saxons arrived! The book also reveals the casual racism of some of Britain’s most fêted historical figures. Both Winston Churchill and Florence Nightingale are shown to have said and done things that are abominable by modern standards.

Ultimately, this is an excellent book that has not been surpassed in breadth or detail since it’s first publication in 1984. It is only sad that Fryer is no longer here to bring out an updated edition, and perhaps to question the publisher’s choice of cover design!

It was in fact his role as a journalist that first piqued his interest in the subject, when he was sent to cover the arrival of the Empire Windrush in 1948. His book ably demonstrates the ignorance of those who believed this was the first arrival of blacks in Britain, and who called for them to go back to where they came from. In fact he shows that there were black people in Britain before the Anglo-Saxons arrived! The book also reveals the casual racism of some of Britain’s most fêted historical figures. Both Winston Churchill and Florence Nightingale are shown to have said and done things that are abominable by modern standards.

Ultimately, this is an excellent book that has not been surpassed in breadth or detail since it’s first publication in 1984. It is only sad that Fryer is no longer here to bring out an updated edition, and perhaps to question the publisher’s choice of cover design!

‘Gustav Ungerer: THE MEDITERRANEAN APPRENTICESHIP OF BRITISH SLAVERY’ Review, TLS, 19 March 2010, p.27.

The British have taken pride in being among the last countries to espouse slavery and one of the first to abolish it. But has there been a tendency to exaggerate the strength of this record? The answer, according to Gustav Ungerer, is that there has been – at least as regards the origins of the British slave trade. In his pithy, trenchant study of this subject, he argues that the beginning of that trade is to be found as far back as the 1480s in the transactions carried out by English merchants then living in Andalusia. This would date it to more than a half-century earlier than the traditional version of history, which likes to present the naval commander and adventurer Sir John Hawkins as the first British slave trader.

Ungerer is at his best in his close – albeit, at times, myopic– analysis of original material unearthed from the Spanish archives, some of which is published at the back of this book. We see how the English merchants integrated into Andalusian society by intermarriage: in 1522, for instance, Thomas Malliard’s daughter Ana married Sancho de Herrera y Sanvedra, the mayor of Sanlucar de Barrameda and governor of its fortress. We see that they owned slaves, in accordance with local custom. Where the author goes too far is in interpreting this Andalusian experience as, to quote from his title, some kind of “apprenticeship” for British slavery. There is an important difference, which he elides, between owning slaves and trading in them. The earliest example of what could be termed transatlantic trade conducted by an English merchant operating out of Andalusia comes in 1521, when Thomas Malliard secured two licences from the Casa de la Contratacion in Seville to ship two black Africans to Santo Domingo. But this is hardly comparable in scale to later voyages, which carried Africans in their hundreds to a life of servitude across the Atlantic.

According to the 16th century English writer Richard Hakluyt, Hawkins learnt his business not from contact with any Andalusian expatriates, but rather from his father and his friends in the Canary Islands. Ungerer suggests Hakluyt may have had a motive for saying this: he wanted to “protect his compatriots against being lumped together with the ignominious record of the Spaniards and Portuguese”. Perhaps, but a 21st-century continental historian may also have his motives, and suffice to say Gustav Ungerer often places more weight on his material than it seems capable of bearing.

Ungerer is at his best in his close – albeit, at times, myopic– analysis of original material unearthed from the Spanish archives, some of which is published at the back of this book. We see how the English merchants integrated into Andalusian society by intermarriage: in 1522, for instance, Thomas Malliard’s daughter Ana married Sancho de Herrera y Sanvedra, the mayor of Sanlucar de Barrameda and governor of its fortress. We see that they owned slaves, in accordance with local custom. Where the author goes too far is in interpreting this Andalusian experience as, to quote from his title, some kind of “apprenticeship” for British slavery. There is an important difference, which he elides, between owning slaves and trading in them. The earliest example of what could be termed transatlantic trade conducted by an English merchant operating out of Andalusia comes in 1521, when Thomas Malliard secured two licences from the Casa de la Contratacion in Seville to ship two black Africans to Santo Domingo. But this is hardly comparable in scale to later voyages, which carried Africans in their hundreds to a life of servitude across the Atlantic.

According to the 16th century English writer Richard Hakluyt, Hawkins learnt his business not from contact with any Andalusian expatriates, but rather from his father and his friends in the Canary Islands. Ungerer suggests Hakluyt may have had a motive for saying this: he wanted to “protect his compatriots against being lumped together with the ignominious record of the Spaniards and Portuguese”. Perhaps, but a 21st-century continental historian may also have his motives, and suffice to say Gustav Ungerer often places more weight on his material than it seems capable of bearing.

Martyr's child: ‘John Guy: A DAUGHTER'S LOVE: THOMAS AND MARGARET MORE’ Review, TLS, 27 February 2009, p. 10.

Thomas More was beheaded on July 6, 1535. His story is well known. The role of his daughter Margaret Roper in that story, less so. John Guy, whose last subject was Mary Queen of Scots, has found a new tragic heroine in Margaret. She seems to be his ideal woman, so much so that his treatment of her husband William Roper seems written from the perspective of a jealous lover. Professor Guy reprimands Roper for failing to provide financial aid to his father in law after he resigned the Chancellorship, and generally deplores his prioritizing of property over principle: “If only William her husband could have given her the love and support she needed, she might have recovered a sense of inner peace[after More’s death], but his grasping, restless mind was fixed on worldly advantage. “

Guy makes a convincing case for Margaret as the great woman behind the great man. Margaret was her father’s main correspondent and confidante, and visited him regularly in the Tower while her mother, Lady Alice, only made the journey once. Her contemporaries extolled Margaret’s virtues as an example of the benefits of education for women. More had her schooled in Latin and Greek alongside her brothers and sisters, in his “school” at Chelsea. At 16, her writings so impressed the Bishop of Exeter that “his countenance showed that his words [of praise] were all too poor to express what he felt”, and whilst still a teenager she was able to correct Erasmus’s edition of the letters of St. Cyprian.

Margaret often remains in the shadows of the narrative however, as do many early modern women: the evidence simply does not exist to tell the full story of their lives. In many cases: “we can only imagine”. Nonetheless, educated imaginings are vital for recovering these untold stories, and it is testament to the maturation of feminist history that a mainstream author such as Guy recognises this. He perhaps goes too far when he suggests that Margaret might have been able to avert the Reformation: “The Church authorities were unable to see that the one person in England... who could match Tyndale as a translator and stylist, and could be relied upon to conform to Catholic teaching and doctrine, was Margaret Roper. But of course, she was a woman, so it never entered their heads”. more

Guy makes a convincing case for Margaret as the great woman behind the great man. Margaret was her father’s main correspondent and confidante, and visited him regularly in the Tower while her mother, Lady Alice, only made the journey once. Her contemporaries extolled Margaret’s virtues as an example of the benefits of education for women. More had her schooled in Latin and Greek alongside her brothers and sisters, in his “school” at Chelsea. At 16, her writings so impressed the Bishop of Exeter that “his countenance showed that his words [of praise] were all too poor to express what he felt”, and whilst still a teenager she was able to correct Erasmus’s edition of the letters of St. Cyprian.

Margaret often remains in the shadows of the narrative however, as do many early modern women: the evidence simply does not exist to tell the full story of their lives. In many cases: “we can only imagine”. Nonetheless, educated imaginings are vital for recovering these untold stories, and it is testament to the maturation of feminist history that a mainstream author such as Guy recognises this. He perhaps goes too far when he suggests that Margaret might have been able to avert the Reformation: “The Church authorities were unable to see that the one person in England... who could match Tyndale as a translator and stylist, and could be relied upon to conform to Catholic teaching and doctrine, was Margaret Roper. But of course, she was a woman, so it never entered their heads”. more

'Imtiaz Habib, Black Lives in the English Archives, 1500-1677: Imprints of the Invisible', Review, Black and Asian Studies Association Newsletter, 52 (September 2008), pp. 28-30.

Imtiaz Habib has done us a great service by providing this accessible database of references to Africans, Indians and Americas in early Modern England and Scotland, many never published before. Their traces are scattered in the documents of the time: their baptisms, marriages and burials were recorded in parish registers, the purchase of their clothes, shoes and other necessaries lie itemised in household accounts, their presence was noted in travel accounts, legal documents and diaries. Habib lists 448 such records of black people (including 32 describing Indian and Native American individuals) from the period 1500-1677. Thus we learn that on the 6th June 1588 ‘Isabell a blackamore’ was buried at St Olave, Hart Street in London; on 16th October 1616, ‘George a blackmore’ married Marie Smith at All Saints Church in Staplehurst, Kent and on 7th September 1665, Samuel Pepys recorded in his diary that over dinner with banker Sir Robert Viner, he was shown ‘a black boy he had that died of a consumption; and being dead, he caused him to be dried in an Oven, and lies there entire in a box.’

However by my calculation, 122 of the 448 records presented are of what Habib describes as ‘fluctuating ethnic clarity’. This phrase is typical of the author’s tendency to use the high-flown register of the American academic literary theorist, which means that readers will require a dictionary to decipher some of his prose. What he means is that he has chosen to extend the benefit of the doubt to all persons with surnames such as ‘Blackmore’, ‘Moore’ and ‘Black’. By these standards, the origin of Sir Thomas More should also be interrogated. He was, after all, nicknamed ‘Niger’ by his friend Erasmus. more

However by my calculation, 122 of the 448 records presented are of what Habib describes as ‘fluctuating ethnic clarity’. This phrase is typical of the author’s tendency to use the high-flown register of the American academic literary theorist, which means that readers will require a dictionary to decipher some of his prose. What he means is that he has chosen to extend the benefit of the doubt to all persons with surnames such as ‘Blackmore’, ‘Moore’ and ‘Black’. By these standards, the origin of Sir Thomas More should also be interrogated. He was, after all, nicknamed ‘Niger’ by his friend Erasmus. more

‘Traces of Shame? Imtiaz Habib: BLACK LIVES IN THE ENGLISH ARCHIVES, 1500-1677’ Review, TLS, 8 August 2008, p. 26.

On the 6th June 1588, 'Isabell a blackamore' was buried at St. Olave, Hart Street in London. On the 16th October 1616, 'George, a blackmore' married Marie Smith at All Saints Church in Staplehurst, Kent. On 7th September 1665, Samuel Pepys recorded in his diary that over dinner with banker Sir Robert Viner, he was shown 'a black boy he had that died of a consumption; and being dead, he caused him to be dried in an Oven, and lies there entire in a box.' Imtiaz Habib, who has previously studied black characters such as Othello in English Renaissance Drama, has listed 448 such records of black people (including thirty-two describing Indian and Native American individuals) in Early Modern England and Scotland. Their traces are scattered in the documents of the time: their baptisms, marriages and burials were recorded in parish registers, the purchase of their clothes, shoes and other necessaries lie itemised in household accounts, their presence was noted in travel accounts, legal documents and diaries. more

‘Derek Wilson: SIR FRANCIS WALSINGHAM: A courtier in an age of terror’ Review, TLS, 14 December 2007, p. 33.

Francis Walsingham kept a stable of sixty horses. These enabled him to maintain the extensive communications network which has earned him the epithet ‘spymaster’. His information was so vital that on his death in 1590, ‘all his papers and bookes both publicke and private were seazed on and carried away’. Those papers relevant to matters of state survive, the private ones do not. His biography is inevitably reduced to a political history of a public man: a life glimpsed through the prism of great events: from the St Bartholomew’s Day Massacre of 1572, which he witnessed, to the execution of Mary Queen of Scots, whom he had proved a traitor. Conyers Read wrote such a biography in 1925. Derek Wilson, in the absence of any new biographical evidence, seeks to reinterpret Walsingham’s times, and through them, his life.

As Wilson explains, Walsingham and Queen Elizabeth had fundamentally different views on policy. He supported a confessional alliance with Protestants abroad; she believed in the divine right of kings. Wilson, seemingly influenced by Walsingham’s complaints about the queen in his letters and by Patrick Collinson’s ‘monarchical republic’ view of the Elizabethan state, unfairly caricatures Elizabeth as a slipper hurling, illogical drama queen, requiring careful managing by her councillors.

Wilson describes an ‘Age of Terror’ in which Pius V is a ‘Roman ayatollah’; Philip II is ‘engaged in a Catholic jihad’; the French Wars of Religion are comparable to the current ‘murderous violence’ between ‘Sunni and Shia Muslims’ and England is full of ‘fundamentalist...cells of immigrant priests’, and Huguenot asylum seekers. At times he shifts to the twentieth century: Henry VIII ruled over a ‘police state’; England and Spain engaged in a ‘cold war’ in the 1570s and 80s and Walsingham’s behaviour is likened to that of ‘Winston Churchill in the 1930s’. A more nuanced evocation of Elizabethan England in her own terms would do more to enhance understanding and facilitate meaningful comparisons.

As Wilson explains, Walsingham and Queen Elizabeth had fundamentally different views on policy. He supported a confessional alliance with Protestants abroad; she believed in the divine right of kings. Wilson, seemingly influenced by Walsingham’s complaints about the queen in his letters and by Patrick Collinson’s ‘monarchical republic’ view of the Elizabethan state, unfairly caricatures Elizabeth as a slipper hurling, illogical drama queen, requiring careful managing by her councillors.

Wilson describes an ‘Age of Terror’ in which Pius V is a ‘Roman ayatollah’; Philip II is ‘engaged in a Catholic jihad’; the French Wars of Religion are comparable to the current ‘murderous violence’ between ‘Sunni and Shia Muslims’ and England is full of ‘fundamentalist...cells of immigrant priests’, and Huguenot asylum seekers. At times he shifts to the twentieth century: Henry VIII ruled over a ‘police state’; England and Spain engaged in a ‘cold war’ in the 1570s and 80s and Walsingham’s behaviour is likened to that of ‘Winston Churchill in the 1930s’. A more nuanced evocation of Elizabethan England in her own terms would do more to enhance understanding and facilitate meaningful comparisons.

‘Susan Ronald: THE PIRATE QUEEN: Elizabeth I, her pirate adventurers and the dawn of Empire’ Review, TLS, 5 October 2007, p. 26.

Deftly interweaving cotemporary accounts with colourful details, Susan Ronald guides us masterfully through an Elizabethan world inhabited by “colourful rapscallions” and “indomitable sea dogs”, who roam the seas seeking plunder, glory and new lands. While these adventurers might be motivated primarily by greed, Elizabeth was in desperate need of cash to finance the defence of her beleaguered realm. The ultimate “success” of her pirates was to undermine the golden foundations of Phillip II’s Spain and to blaze a trail towards a British empire.

Every good story needs a dashing hero, and the “ingenious” Sir Francis Drake dominates this narrative. Drake himself worried that “You will say that this man who steals by day and prays by night in public is a devil”, but his has nothing to fear from Ronald, who similarly cannot hide her affection for the “vintage” brilliance of Queen Elizabeth.

Ronald tells her story well, but it is a time-worn tale. It was told first by Elizabethan pamphleteers and Spaniards who felt less inadequate in the face of an invincible foe. It was told again by the Victorians, seeking precedents for their own imperial ambitions. We have romanticized pirates: Tudor wordlists define “pirate” as simply “robber by sea”. When the Spanish admiral Santa Cruz branded Elizabeth I the “pirate queen”, it wasn’t meant as a compliment. Pirates still exist: since 2002, the International Maritime Bureau has recorded 258 pirate attacks in the treacherous Malacca Strait (which Drake sailed close to in 1579). Ronald does not quite manage to shrug off the “heroic pirate” myth to produce a clear-eyed account.

In a year in which we commemorate the abolition of the slave trade and sixty years of Indian independence, we cannot ignore the fact that Sir John Hawkins and his backers sought profit from human cargoes, while Drake and Raleigh claimed territory for their Queen that was already inhabited. There is a new story that is emerging in current scholarship, which remains to be told to a wider audience, as multifaceted as any pirate’s plundered diamonds. It is the painful, but hopefully more truthful, story of how these early encounters between Europeans and non-Europeans in the sixteenth century shaped the challenging world we live in today.

Every good story needs a dashing hero, and the “ingenious” Sir Francis Drake dominates this narrative. Drake himself worried that “You will say that this man who steals by day and prays by night in public is a devil”, but his has nothing to fear from Ronald, who similarly cannot hide her affection for the “vintage” brilliance of Queen Elizabeth.

Ronald tells her story well, but it is a time-worn tale. It was told first by Elizabethan pamphleteers and Spaniards who felt less inadequate in the face of an invincible foe. It was told again by the Victorians, seeking precedents for their own imperial ambitions. We have romanticized pirates: Tudor wordlists define “pirate” as simply “robber by sea”. When the Spanish admiral Santa Cruz branded Elizabeth I the “pirate queen”, it wasn’t meant as a compliment. Pirates still exist: since 2002, the International Maritime Bureau has recorded 258 pirate attacks in the treacherous Malacca Strait (which Drake sailed close to in 1579). Ronald does not quite manage to shrug off the “heroic pirate” myth to produce a clear-eyed account.

In a year in which we commemorate the abolition of the slave trade and sixty years of Indian independence, we cannot ignore the fact that Sir John Hawkins and his backers sought profit from human cargoes, while Drake and Raleigh claimed territory for their Queen that was already inhabited. There is a new story that is emerging in current scholarship, which remains to be told to a wider audience, as multifaceted as any pirate’s plundered diamonds. It is the painful, but hopefully more truthful, story of how these early encounters between Europeans and non-Europeans in the sixteenth century shaped the challenging world we live in today.

‘Sally Varlow: THE LADY PENELOPE: The lost tale of Love and Politics in the Court of Elizabeth I’ Review, TLS, 13 July 2007, p. 29.

Found guilty of treason in February 1601, Robert Devereux, Earl of Essex, named amongst his co-conspirators “one who is nearest to me, my sister, who did continually urge me on”. Penelope, wife to the aptly-named Lord Rich, narrowly evaded punishment, primarily because her lover, Lord Mountjoy, commanded the army in Ireland. More often remembered as the court beauty who inspired Philip Sidney’s Astrophel and Stella, Penelope was, as Sally Varlow demonstrates here, a key political figure at the Elizabethan court.

Varlow has discovered an inscription in Sir Francis Knollys’s Latin Dictionary which suggests that his wife, Katherine Carey, Penelope and Essex’s grandmother, was fathered by Henry VIII. However, this is more relevant to the life of Carey than to that of her granddaughter. Penelope’s influence derived more directly from her persuasive character and powerful connections. Her thirty-three extant letters show the everyday wielding of this influence in the form of patronage, but sadly this is not explored. Varlow’s judgements follow uncritically the Devereux’s views of political life, so that she vilifies the Cecils and Queen Elizabeth, while honeying over the treasonous behaviour of Penelope and Essex and their friends.

Varlow is happiest discussing Penelope’s personal life, notably her perculiarly public affair with Mountjoy: while still married she bore him five children, naming the eldest son “Montjoy”. Penelope’s homes at Chartley, Leighs Priory and Wanstead are described with a travel-writer’s flair for evocative detail. The speculations on Penelope’s feelings are, however, less convincing, and not helped by the author’s populist prose : “No one knows what Penelope thought, but her heart must have ached”.

Varlow laments that at the end of Penelope’s life, and ever since, there has been “no one to ride out as her champion and defend her honour”, as Mountjoy had at the Ascension Day tilts in 1590. Varlow’s quest to resurrect the reputation of her subject is a noble one, but she lacks the eloquence and analytical powers (“plays were the new black”) necessary fully to succeed in it.

Varlow has discovered an inscription in Sir Francis Knollys’s Latin Dictionary which suggests that his wife, Katherine Carey, Penelope and Essex’s grandmother, was fathered by Henry VIII. However, this is more relevant to the life of Carey than to that of her granddaughter. Penelope’s influence derived more directly from her persuasive character and powerful connections. Her thirty-three extant letters show the everyday wielding of this influence in the form of patronage, but sadly this is not explored. Varlow’s judgements follow uncritically the Devereux’s views of political life, so that she vilifies the Cecils and Queen Elizabeth, while honeying over the treasonous behaviour of Penelope and Essex and their friends.

Varlow is happiest discussing Penelope’s personal life, notably her perculiarly public affair with Mountjoy: while still married she bore him five children, naming the eldest son “Montjoy”. Penelope’s homes at Chartley, Leighs Priory and Wanstead are described with a travel-writer’s flair for evocative detail. The speculations on Penelope’s feelings are, however, less convincing, and not helped by the author’s populist prose : “No one knows what Penelope thought, but her heart must have ached”.

Varlow laments that at the end of Penelope’s life, and ever since, there has been “no one to ride out as her champion and defend her honour”, as Mountjoy had at the Ascension Day tilts in 1590. Varlow’s quest to resurrect the reputation of her subject is a noble one, but she lacks the eloquence and analytical powers (“plays were the new black”) necessary fully to succeed in it.