History

I researched 'Africans in Britain, 1500-1640' at Oxford and my first book, Black Tudors: The Untold Story, was published by Oneworld in October 2017. The TV rights have been optioned by Silverprint Pictures, who are now developing a drama series, 'Southwark', with BritBox; and the book was shortlisted for the 2018 Wolfson History Prize and the 2018 Nayef Al-Rodhan Prize. Here you can read my published academic journal articles and contributions to reference works, as well as the odd historical snippet in the broadsheets, and some guest blogs. I also review history books for the TLS and others. To read about my history talks, click here. I also write about history on my blog.

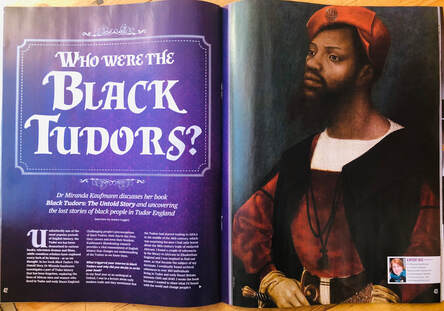

Who Were The Black Tudors?, All About History, Issue 96, October 2020, pp. 42-47.

Undoubtedly one of the most popular periods of English history, the Tudor era has been dramatised in various books, television dramas and films, while countless scholars have explored every inch of its history - or so we thought. In her book Black Tudors: The Untold Story, Dr. Miranda Kaufmann investigates a part of Tudor history that has been forgotten, exploring the lives of African men and women who lived in Tudor and early stuart England.

Challenging people's preconceptions of black Tudors, their day-to-day lives, their careers and even their freedom, Kaufmann's illuminating research provides a vital reassessment of English history that changes our understanding of the Tudors as we know them.

What triggered your interest in black Tudors and why did you decide to write the book?

In my final year as an undergrad at Oxford I was in a lecture about early modern trade and they mentioned that the Tudors had started trading to Africa in the middle of the sixteenth century... more

Challenging people's preconceptions of black Tudors, their day-to-day lives, their careers and even their freedom, Kaufmann's illuminating research provides a vital reassessment of English history that changes our understanding of the Tudors as we know them.

What triggered your interest in black Tudors and why did you decide to write the book?

In my final year as an undergrad at Oxford I was in a lecture about early modern trade and they mentioned that the Tudors had started trading to Africa in the middle of the sixteenth century... more

'Tudor Women: African Women in Tudor England', WC1E, Issue 3, 2018, pp. 46-47.

Dr Miranda Kaufmann, a senior research fellow at the Institute of Commonwealth Studies, provides a tantalising glimpse into the lives of some of the pioneering African women who lived and worked in 16th- and early 17th-century England.

The presence of African women (and men) in 16th- and early 17th-century England shows that black British history stretches back centuries. They lived in a world where skin colour was less important than religion, class or talent – before the English became heavily involved in the slave trade, and before they had properly established colonies in the Americas. The stories of these women demonstrate resilience, resourcefulness and a desire to integrate. more

The presence of African women (and men) in 16th- and early 17th-century England shows that black British history stretches back centuries. They lived in a world where skin colour was less important than religion, class or talent – before the English became heavily involved in the slave trade, and before they had properly established colonies in the Americas. The stories of these women demonstrate resilience, resourcefulness and a desire to integrate. more

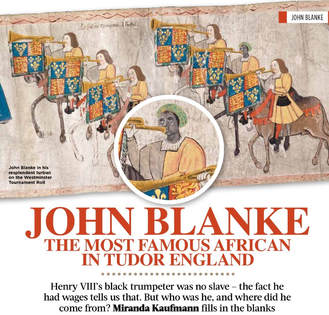

'John Blanke', History Revealed, Issue 58, August 2018, pp. 61-63.

Although at least 200 Africans lived in Tudor England, John Blanke is the only one for whom we have a portrait. Indeed he appears twice in the Westminster Tournament Roll, a 60ft long vellum manuscript commissioned by Henry VIII in 1511. It was his proximity to the King that explains why he was portrayed. For John Blanke had worked at the Tudor court as a trumpeter to Henry VII and Henry VIII since at least 1507. We know that because there are a series of records of him being paid wages. The first of these dates to early December 1507, when he was paid 20s for the month of November, so at a rate of 8d a day. That meant his annual salary was £12, three times the average servant’s wage.

We don’t know how John Blanke came to England, but the most likely explanation is that he arrived from Spain in the retinue of Katherine of Aragon when she came to England in 1501 to marry Prince Arthur, Henry VIII’s older brother. There were many Africans in Spain. Between 1441 and 1521, an estimated 156,000 Africans arrived in Spain, Portugal and the Atlantic islands. By 1550, Africans made up 7.5% of the population of Seville. In 1574, the city was described as ‘a giant chessboard containing an equal number of white and black chessmen’. So it makes sense that Katherine could have had a black trumpeter in her entourage. more

We don’t know how John Blanke came to England, but the most likely explanation is that he arrived from Spain in the retinue of Katherine of Aragon when she came to England in 1501 to marry Prince Arthur, Henry VIII’s older brother. There were many Africans in Spain. Between 1441 and 1521, an estimated 156,000 Africans arrived in Spain, Portugal and the Atlantic islands. By 1550, Africans made up 7.5% of the population of Seville. In 1574, the city was described as ‘a giant chessboard containing an equal number of white and black chessmen’. So it makes sense that Katherine could have had a black trumpeter in her entourage. more

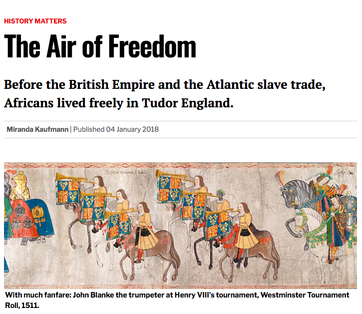

‘The Air of Freedom’, History Today, 4 January 2018, pp. 18-20.

Juan Gelofe, an enslaved 40-year-old Wolof man from West Africa, had a conversation with an English sailor, William Collins, in a Mexican silver mine in 1572. Juan remarked that England ‘must be a good country as there were no slaves there’. Collins confirmed: ‘It was true, that there they were all freemen.’ Spanish officials sang the same tune: in 1586 Pedro de Arana wrote to the Spanish House of Trade from Havana, commenting that in Francis Drake’s country ‘negro labourers’ were free.

When the question arose in an English court of law in 1569, it was resolved ‘that England has too pure an Air for Slaves to breathe in’. This was consistent with the absence of any legislation on the status of slavery under English law. Parliament never issued any law codes delineating slavery to compare with the Portuguese Ordenações Manuelinas (1481-1514), the Dutch East India Ordinances (1622), France’s Code Noir (1685) or the codes that appeared in Virginia and other American states from the 1670s.

Instead, arrival on English soil set one free. more

When the question arose in an English court of law in 1569, it was resolved ‘that England has too pure an Air for Slaves to breathe in’. This was consistent with the absence of any legislation on the status of slavery under English law. Parliament never issued any law codes delineating slavery to compare with the Portuguese Ordenações Manuelinas (1481-1514), the Dutch East India Ordinances (1622), France’s Code Noir (1685) or the codes that appeared in Virginia and other American states from the 1670s.

Instead, arrival on English soil set one free. more

‘Black Faces of Tudor England’, BBC History Magazine, November 2017, pp. 41-44.

Mary Fillis, as imagined by Rose Wilkinson

Mary Fillis, as imagined by Rose Wilkinson

From the court musician who persuaded Henry VIII to give him a handsome pay rise,

to the family man who profited from high society’s passion for silk stockings,

Miranda Kaufmann profiles six Africans who called England home in the 16th century... more

to the family man who profited from high society’s passion for silk stockings,

Miranda Kaufmann profiles six Africans who called England home in the 16th century... more

“Making the Beast with two Backs” – Interracial Relationships in Early Modern England, Literature Compass, 12.1, January 2015, pp. 22-37.

Othello and Desdemona

Othello and Desdemona

Abstract: Shakespeare's tragedy of Othello and Desdemona has long attracted critics to consider the issues of interracial relationships and miscegenation in early modern England. More recently, other black characters have been found in Renaissance literature and an African presence in 16th and 17th century England has been demonstrated from archival sources. This article gives an overview of these developments and their implications for the study of interracial relationships in early modern literature. Evidence from the archives is brought to bear on different aspects of relationships both between black men and white women and between black women and white men. This new information about interracial marriages, as well as sexual intercourse or “fornication”, prostitution and the resulting mixed race children must be incorporated into the discussion of interracial relationships in Renaissance literature.

Read the full article here.

Read the full article here.

My Favourite Place: Cartagena de Indias, Colombia, BBC History Magazine, December 2014, pp. 84-85.

St. Pedro Claver with an enslaved Angolan

St. Pedro Claver with an enslaved Angolan

I’ve only visited Cartagena de Indias once, but it cast an enduring spell on me. I arrived in the old walled city after dark. Wandering past colourful Spanish colonial houses, their balconies overflowing with bright pink bougainvillea, I was seduced by the music echoing through the cobbled streets. Like the city itself, the music was a fusion of cultures: the dancers below the statue of Simón Bolívar (Venezuelan leader, and president of Gran Colombia from 1819–30) moved to the sounds of African drumbeats and South American pipes.

Standing beneath the statue of India Catalina – outside the city wall – it’s hard not to be reminded that indigenous peoples inhabited this area for some 5,000 years before the Spanish arrived. Catalina was the daughter of a Kalamari chieftain, and was captured in 1509. She was baptised and learnt Spanish, later acting as a translator for Pedro de Heredia when he founded the city in 1533. The help she gave this conquistador, who plundered the wealth of her people, still divides opinion as to whether she should be remembered as a heroine or a traitor. Cartagena became one of the richest trading ports in Spanish America – gold and silver mined from across the continent was loaded into galleons here en route to Spain. It was also one of two ports authorised by the Spanish crown to trade in enslaved Africans. At the peak of the trade, at least a thousand slaves were sold in the triangular Plaza de las Coches – now a popular tourist hub, lined with sweet stalls – every month. more

Standing beneath the statue of India Catalina – outside the city wall – it’s hard not to be reminded that indigenous peoples inhabited this area for some 5,000 years before the Spanish arrived. Catalina was the daughter of a Kalamari chieftain, and was captured in 1509. She was baptised and learnt Spanish, later acting as a translator for Pedro de Heredia when he founded the city in 1533. The help she gave this conquistador, who plundered the wealth of her people, still divides opinion as to whether she should be remembered as a heroine or a traitor. Cartagena became one of the richest trading ports in Spanish America – gold and silver mined from across the continent was loaded into galleons here en route to Spain. It was also one of two ports authorised by the Spanish crown to trade in enslaved Africans. At the peak of the trade, at least a thousand slaves were sold in the triangular Plaza de las Coches – now a popular tourist hub, lined with sweet stalls – every month. more

What’s Happening in Black British History? A Conversation, a guest blog for the School of Advanced Study, University of London, 18th November 2014.

There was a buzz at the Senate House headquarters of the School of Advanced Study (SAS) on 30 October, as at least one hundred people gathered in Chancellor’s Hall to spend the day discussing, ‘What’s Happening in Black British History?’

The event has since been described as ‘exciting, informative, culturally enriching’, ‘impressively attended, very buoyant and well-informed’. It has also been praised for its ‘sense of warmth and informality within academic discourses’ and ‘clear rigour without elitism’.

Attendees included pioneers of the subject who have been writing about Black British History for more than 30 years, young academics forging new paths, teachers, students, artist Ebun Culwin, and representatives of public bodies such as English Heritage and the Heritage Lottery Fund.

The workshop was the first in a series designed to develop the conversation about Black British History. It was organised by Michael Ohajuru and myself at the invitation of Professor Philip Murphy, director of the Institute of Commonwealth Studies and Deputy Dean of SAS. Future events are planned for 2015 in venues outside London during February and May half terms, and we aim to establish a national network of Black British History researchers and communicators. more

The event has since been described as ‘exciting, informative, culturally enriching’, ‘impressively attended, very buoyant and well-informed’. It has also been praised for its ‘sense of warmth and informality within academic discourses’ and ‘clear rigour without elitism’.

Attendees included pioneers of the subject who have been writing about Black British History for more than 30 years, young academics forging new paths, teachers, students, artist Ebun Culwin, and representatives of public bodies such as English Heritage and the Heritage Lottery Fund.

The workshop was the first in a series designed to develop the conversation about Black British History. It was organised by Michael Ohajuru and myself at the invitation of Professor Philip Murphy, director of the Institute of Commonwealth Studies and Deputy Dean of SAS. Future events are planned for 2015 in venues outside London during February and May half terms, and we aim to establish a national network of Black British History researchers and communicators. more

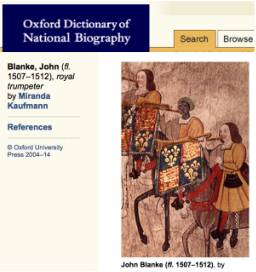

‘Blanke, John (fl. 1507–1512)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, September 2014.

Blanke, John (fl. 1507–1512), royal trumpeter, was employed as a musician at the courts of Henry VII and Henry VIII, making his first recorded appearance there in 1507. He is thought to have been of African descent, but his age, place of birth, and parentage are unknown. His surname may have originated as a nickname, derived from the word blanc in French or blanco in Spanish, both meaning ‘white’. Blanke was part of a wider trend for European rulers to employ African musicians, dating from at least 1194, when turbaned black trumpeters heralded the entry of the Holy Roman emperor Henry VI into Palermo in Sicily. It has been suggested that Blanke arrived in England with Katherine of Aragon when she came to marry Arthur, prince of Wales, in 1501. While there is no record of Blanke's arrival, there is evidence of other Africans in Katherine's retinue, including Catalina de Cardones, who was born in Motril, Granada. However, the Tudor court employed musicians from across continental Europe, and Blanke may have come from Spain, Portugal, or Italy, all of which had growing African populations at this time. more

Out & About: History Explorer: Africans in Tudor and Stuart Britain, BBC History Magazine, April 2014, pp. 80-83.

After knighting Francis Drake in 1581, Queen Elizabeth commanded that the Golden Hind, the ship in which he had circumnavigated the globe – the first Englishman to do so – be lodged in a dock in Deptford as “a monument to all posterity of that famous and worthy exploite”.

Drake’s ship was broken up a century later, but the replica docked in the pretty Devon harbour of Brixham transported me, with a creak of timber and a whiff of salt and tar, back to the world of those Elizabethan sea dogs. Drake’s story, of course, has been told many times. What is far less well known is the story of the Africans who sailed aboard the Golden Hind. more

Drake’s ship was broken up a century later, but the replica docked in the pretty Devon harbour of Brixham transported me, with a creak of timber and a whiff of salt and tar, back to the world of those Elizabethan sea dogs. Drake’s story, of course, has been told many times. What is far less well known is the story of the Africans who sailed aboard the Golden Hind. more

Call and Responses: The Odyssey of the Moor: interview with Graeme Mortimer Evelyn, History Today, 20th December 2013.

|

|

This is a video interview with Graeme Mortimer Evelyn about his installation, Call and Responses: The Odyssey of the Moor, on display at Kensington Palace until 6th January 2014.

Graeme's work is a response to Dutch master sculptor John van Nost’s Bust of the Moor, commissioned by King William III in around 1689, the same year he invaded England. My thanks to Dean Nicholas and Charlotte Crow of History Today, Historic Royal Palaces, the Royal Collection Trust and Arts Council England for their assistance in producing this video. |

Georgians Unrevealed, a guest blog for UCL's Legacies of British Slave-ownership project, 20th December 2013.

“Win a luxury country break”: a prize that would no doubt have appealed to those who received compensation for relinquishing their slaves in 1834 as much as it does to those visiting the new Georgians Revealed exhibition at the British Library today. One man who received compensation in 1834 might have been particularly surprised to see this notice at the back of the exhibition guide. For what is advertised as the “Four Seasons Hotel Hampshire”, he would have recognized as Dogmersfield Park, his childhood home. Having recently reviewed Madge Dresser and Andrew Hann’s new book Slavery and the British Country House for the TLS, I was immediately curious about the history of this Georgian house, now a luxury hotel. A few minutes with the Legacies of British Slave-ownership database confirmed my suspicions that it, like many other country houses built in the Georgian period, can be linked to the history of transatlantic slavery.

Humphrey St. John Mildmay (1794-1853) was one of five beneficiaries from Barings Bank who received over £50,000 in compensation between them, in relation to 1015 enslaved Africans working on seven different estates in British Guiana. When I was surveying English Heritage properties for links to slavery back in 2006, Nick Draper’s research was one of my first ports of call. In this case, it again provides a way into a wider story of how slavery-related wealth and colonial experience pervaded the lives of those who lived in places like Dogmersfield Park. more

Humphrey St. John Mildmay (1794-1853) was one of five beneficiaries from Barings Bank who received over £50,000 in compensation between them, in relation to 1015 enslaved Africans working on seven different estates in British Guiana. When I was surveying English Heritage properties for links to slavery back in 2006, Nick Draper’s research was one of my first ports of call. In this case, it again provides a way into a wider story of how slavery-related wealth and colonial experience pervaded the lives of those who lived in places like Dogmersfield Park. more

The Black Face of Renaissance Europe, History Today, 21st May 2013.

In the case of Giulia de’ Medici, the African presence was literally painted out of European history for almost four hundred years. The granddaughter of an enslaved African woman named Simonetta, Giulia was portrayed by Jacopo Pontormo in 1539 with her guardian, Maria Salviati. Her father, Alessandro de’ Medici, Duke of Florence, had been assassinated two years before. At some point in the following century, her image was painted over. The child uncovered during cleaning in 1937 was only identified as Giulia in 1992. Pontormo’s portrait is thus the earliest of a child of African descent in Europe, and became the inspiration for this exhibition, which includes those of African descent, like Giulia, in its definition of “African”.

Just as we have only recently re-discovered Giulia, we are also only just beginning to learn about the Africans who arrived in Europe during the “long sixteenth century,” from around 1480 to 1610. This exhibition is full of revelation, especially for an audience so unused to the idea of Africans in Europe that I heard someone refer to the “African-American” exhibition. more

Just as we have only recently re-discovered Giulia, we are also only just beginning to learn about the Africans who arrived in Europe during the “long sixteenth century,” from around 1480 to 1610. This exhibition is full of revelation, especially for an audience so unused to the idea of Africans in Europe that I heard someone refer to the “African-American” exhibition. more

We need Mary Seacole as well as Queen Mary, The Times, 11th January 2013.

Apart from learning our dates, let’s also know that Henry VIII had a black trumpeter

One of the party slogans inNineteen Eighty-Four is: “Who controls the past controls the future. Who controls the present controls the past.” The latest skirmish over control of the past is whether black Britons such as Mary Seacole and Olaudah Equiano should be dropped from the history curriculum.

The Education Secretary wants to give children “the opportunity to hear our island story”. So in the name of traditional history, out go Seacole and Equiano. Jesse Jackson, with a host of other left-wing names, claimed in a letter to The Times this week that to remove them from the curriculum was “historically and culturally incorrect”. A more extreme voice suggested that Michael Gove’s desire to see children learning the names and dates of the kings and queens of England was as outmoded as “fagging and Latin”. more

One of the party slogans inNineteen Eighty-Four is: “Who controls the past controls the future. Who controls the present controls the past.” The latest skirmish over control of the past is whether black Britons such as Mary Seacole and Olaudah Equiano should be dropped from the history curriculum.

The Education Secretary wants to give children “the opportunity to hear our island story”. So in the name of traditional history, out go Seacole and Equiano. Jesse Jackson, with a host of other left-wing names, claimed in a letter to The Times this week that to remove them from the curriculum was “historically and culturally incorrect”. A more extreme voice suggested that Michael Gove’s desire to see children learning the names and dates of the kings and queens of England was as outmoded as “fagging and Latin”. more

Slavery shouldn't distort the story of black people in Britain, The Guardian, 17th October 2012.

Sir John Hawkins (1532-1595)

When I tell people I study Africans in Renaissance Britain, they often reply: "Oh, you mean slaves?" Despite the fact that Black History Month – currently being celebrated – is now in its 25th year, and that it's more than 60 years since the Windrush brought the first postwar Caribbean migrants, it's clear that many wrong assumptions about the black presence in Britain are still made.

It seems the emphasis on the horrors of slavery, including the commemoration of the Abolition of the Slave Trade Act's bicentenary in 2007, can leave many, especially the young, with a very bleak image of black history. The assumption that Africans in 16th- and 17th-century England must have been slaves is not only wrong, but dangerous. more

It seems the emphasis on the horrors of slavery, including the commemoration of the Abolition of the Slave Trade Act's bicentenary in 2007, can leave many, especially the young, with a very bleak image of black history. The assumption that Africans in 16th- and 17th-century England must have been slaves is not only wrong, but dangerous. more

Africans in early modern London: Tales from London Metropolitan Archives (LMA) , 25th July 2012.

Miranda Kaufmann shares some of the stories she has uncovered whilst researching her Oxford D.Phil thesis on ‘Africans in Britain, 1500-1640’.

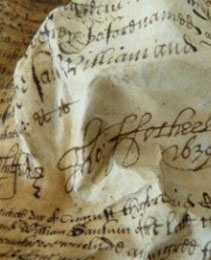

In September 1615, a Ratcliffe mariner named Thomas Jeronimo, his wife Helen and a musician named John Anthony all appeared at the Middlesex Quarter Sessions. Helen was suspected of stealing ‘14 bookes of callikoe, 26 pieces of pachers and 108 lb. of suger’ from a merchant named Francis Pinto. Both men were described as ‘Maurus’ - meaning ‘moor’. (LMA MJ/SR/S53, nos. 112, 113; British History Online.)

Unfortunately, no further details of this case survive. It is one of many tantalising glimpses of the lives of Africans in early modern London that can be found in the records held at London Metropolitan Archives (LMA). The majority of the evidence comes from the parish registers, where the baptisms, marriages and burials of Africans were recorded. The Black and Asian Londoners Project, which ran from 2001 until 2003 at LMA, found over 2,000 references to Black or Asian Londoners in the baptism registers of the ancient parishes of London and Middlesex between 1597 and 1856. Since most of the records previously held at Guildhall Library have been transferred to LMA, the visitor also now has access to the entries from the City of London parishes which are being searched from 1538-1837 in a partner project (still on-going), many of which have been transcribed here. A gem of this collection is the parish register of St. Botolph Aldgate, whose clerk, Thomas Harridance, gave unusually detailed descriptions, such as that of the baptism of Mary Phyllis on 3 June 1597. LMA also holds microfilms of the Bridewell Court Books, which contain some colourful snippets, such as the presentment in March 1628 of ‘Peter Cavandigoe...a Blackmore for being an idle and wandring p[er]son and for breaking a boyes leg with a broome staffe as the boy past along street not giving him any cause of offence’. (CLC/275/MS/33011/007 f.65v.) more

In September 1615, a Ratcliffe mariner named Thomas Jeronimo, his wife Helen and a musician named John Anthony all appeared at the Middlesex Quarter Sessions. Helen was suspected of stealing ‘14 bookes of callikoe, 26 pieces of pachers and 108 lb. of suger’ from a merchant named Francis Pinto. Both men were described as ‘Maurus’ - meaning ‘moor’. (LMA MJ/SR/S53, nos. 112, 113; British History Online.)

Unfortunately, no further details of this case survive. It is one of many tantalising glimpses of the lives of Africans in early modern London that can be found in the records held at London Metropolitan Archives (LMA). The majority of the evidence comes from the parish registers, where the baptisms, marriages and burials of Africans were recorded. The Black and Asian Londoners Project, which ran from 2001 until 2003 at LMA, found over 2,000 references to Black or Asian Londoners in the baptism registers of the ancient parishes of London and Middlesex between 1597 and 1856. Since most of the records previously held at Guildhall Library have been transferred to LMA, the visitor also now has access to the entries from the City of London parishes which are being searched from 1538-1837 in a partner project (still on-going), many of which have been transcribed here. A gem of this collection is the parish register of St. Botolph Aldgate, whose clerk, Thomas Harridance, gave unusually detailed descriptions, such as that of the baptism of Mary Phyllis on 3 June 1597. LMA also holds microfilms of the Bridewell Court Books, which contain some colourful snippets, such as the presentment in March 1628 of ‘Peter Cavandigoe...a Blackmore for being an idle and wandring p[er]son and for breaking a boyes leg with a broome staffe as the boy past along street not giving him any cause of offence’. (CLC/275/MS/33011/007 f.65v.) more

‘SIR PEDRO NEGRO: What colour was his skin?’, Notes and Queries, Vol. 253, no. 2 (June 2008), pp.142-146.

IN a footnote to a recent article,1 Gustav Ungerer concludes that ‘the career of the Spanish mercenary Pedro Negro under king Henry VIII is quite irrelevant to the study of the ideological conception of Othello’ because none of the available contemporary records ‘mentions that Sir Peter Negro was black’. He argues that Negro was more likely to belong to a Genoese family of that name that had settled in Spain and Portugal in the course of the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries. This contradicts those who have taken this Spanish mercenary, knighted by Protector Somerset in 1548, as evidence that it was possible for a black man to gain prestige and honour in sixteenth-century Britain. The chief protagonist of Negro's blackness is literary critic Imtiaz Habib, who draws a parallel between Negro and Othello: ‘Shakespeare's Othello should be considered … in the context of black military service in Tudor armies and generally, of the unacknowledged blacks of sixteenth century England’.2

This is not a straightforward academic disagreement. Habib's rhetoric is infused with the underlying accusation that evidence of black mercenaries serving in the Tudor army has been suppressed by white imperialists: ‘This [black] presence is the site of suppressive inscription that is the modality of empire building’.3 He has recently remarked: ‘Its also interesting that whenever any claim of historical significance is made for a Black person in early modern Europe, the blackness of the person has to be immediately challenged. It would appear that even though oppressed, and denigrated in life a Black person has to prove her/his blackness for European history to even acknowledge her/his existence, whereas a White person is White by default and all significance is hers/his automatically.’4 While this polemic approach is unhelpful, Ungerer's proof by omission is not sufficient to disprove Negro's blackness. Contemporary chroniclers may have seen the name Negro as indication enough that the soldier was black. In this article, I will revisit the evidence for the career of Sir Pedro Negro, including discussion for the first time of his will, his coat of arms, and a letter written in 1549 by Marion, Lady Hume, in order to re-examine the question of his skin colour. more

This is not a straightforward academic disagreement. Habib's rhetoric is infused with the underlying accusation that evidence of black mercenaries serving in the Tudor army has been suppressed by white imperialists: ‘This [black] presence is the site of suppressive inscription that is the modality of empire building’.3 He has recently remarked: ‘Its also interesting that whenever any claim of historical significance is made for a Black person in early modern Europe, the blackness of the person has to be immediately challenged. It would appear that even though oppressed, and denigrated in life a Black person has to prove her/his blackness for European history to even acknowledge her/his existence, whereas a White person is White by default and all significance is hers/his automatically.’4 While this polemic approach is unhelpful, Ungerer's proof by omission is not sufficient to disprove Negro's blackness. Contemporary chroniclers may have seen the name Negro as indication enough that the soldier was black. In this article, I will revisit the evidence for the career of Sir Pedro Negro, including discussion for the first time of his will, his coat of arms, and a letter written in 1549 by Marion, Lady Hume, in order to re-examine the question of his skin colour. more

‘Caspar van Senden, Sir Thomas Sherley and the ‘Blackamoor’ Project’, Historical Research, vol. 81, no. 212 (May 2008), pp. 366-371.

Abstract: This article investigates the project of Caspar Van Senden, a Lubeck merchant, and his patron Sir Thomas Sherley, who sought crown permission to collect ‘blackamoores and negars’ in England and sell them in Lisbon. By examining the reports of Robert Cecil’s agent in Lisbon and letters written to Cecil by Van Senden and Sherley, it explains how unsuccessful their project was, and how it may have had political as well as financial motivation. It also reinterprets the Privy Council order of 1596, and concludes that a similar document of 1601, conventionally listed as a proclamation is likely never to have gone beyond draft form. The article concludes that Elizabeth’s government never envisaged an expulsion of blacks, but was merely trying to fend off another debtor with a patent. more

Slavery connections and new perspectives: English Heritage properties, Conservation Bulletin, Issue 58 (Summer 2008) pp. 10-11.

Brodsworth Hall, Yorkshire.

‘Leaving this room, we arrive in the colonial suite, inlaid entirely with rarest marble and raw silk wall coverings. At today’s prices, this room would cost over £40M to decorate. And how did Sir Henry earn this sort of money? Slavery.

So if you like this room, if you even for a fleeting instant thought ‘Ooh, looks nice’, then you like slavery. You racist! ’

‘Audio guide to “Historic Hibsworth Hall”’ audio-guide parody, That Mitchell and Webb Sound, (broadcast on BBC Radio 4 21/7/07, 18.30).

Inspired by the bicentenary of the Parliamentary abolition of the British slave trade, English Heritage recently commissioned a survey to identify links between 33 of its properties which were been built or occupied in the main era of English slave trading (c 1640–1840) and slavery or abolition. The intention was to establish what form any such links took and to add this to the bank of historical research on which future site interpretation can be based. Of the 33 properties surveyed, 26 were found to have some sort of link to the history of slavery and abolition.

The kinds of connections uncovered were much more diverse than the stereotype of a wealthy slave trader or colonial plantation owner building himself a country house on the profits of exploitation. In fact none of the properties were directly built from the proceeds of slavery in this way. more

So if you like this room, if you even for a fleeting instant thought ‘Ooh, looks nice’, then you like slavery. You racist! ’

‘Audio guide to “Historic Hibsworth Hall”’ audio-guide parody, That Mitchell and Webb Sound, (broadcast on BBC Radio 4 21/7/07, 18.30).

Inspired by the bicentenary of the Parliamentary abolition of the British slave trade, English Heritage recently commissioned a survey to identify links between 33 of its properties which were been built or occupied in the main era of English slave trading (c 1640–1840) and slavery or abolition. The intention was to establish what form any such links took and to add this to the bank of historical research on which future site interpretation can be based. Of the 33 properties surveyed, 26 were found to have some sort of link to the history of slavery and abolition.

The kinds of connections uncovered were much more diverse than the stereotype of a wealthy slave trader or colonial plantation owner building himself a country house on the profits of exploitation. In fact none of the properties were directly built from the proceeds of slavery in this way. more

The Legacy of 2007: Looking Forward, Historic House, Spring 2008, pp.37-38.

Hartsheath, North Wales.

Hartsheath, North Wales.

Last year I inherited a historic house in North Wales and was chosen by English Heritage to research the links between their properties and slavery. In the course of the latter, I discovered that in the former I had inherited not just a beautiful house but a controversial legacy. North Wales is, after all, far too close to Liverpool for at least some of its families not to have been linked to the Slave Trade. Thus I have watched the events and debates of this year with a personal as well as an academic interest.

It is often asserted that all stately homes were built on the proceeds of the Slave Trade. This is patently too broad a generalisation to be true in every case. Of the 33 properties in the custody of English Heritage built or occupied between 1600 and 1840, I found eight that had no demonstrable link to Slavery. I looked for a wide range of possible connections, from the obvious family ownership of plantations or involvement in slave trading, to more indirect links, such as marriages to ‘West Indian’ heiresses, investment in the South Sea Bubble, or involvement (on either side of the debate) in the Parliamentary process which led to abolition. This was an initial survey of the secondary literature and various databases, including one detailing the individuals who were paid reparations for the loss of their enslaved ‘property’ in 1834. Further examination of house archives, furnishings and architecture would provide further or new evidence of these connections. This is a story that needs to be told in full, for all the houses in this country, whether they are cared for by English Heritage, the National Trust or private owners. Then, in 2033, we will be better able to commemorate the Abolition of Slavery, as opposed to the Slave Trade. We will also be better equipped to make informed judgements on the issues that arise. more

It is often asserted that all stately homes were built on the proceeds of the Slave Trade. This is patently too broad a generalisation to be true in every case. Of the 33 properties in the custody of English Heritage built or occupied between 1600 and 1840, I found eight that had no demonstrable link to Slavery. I looked for a wide range of possible connections, from the obvious family ownership of plantations or involvement in slave trading, to more indirect links, such as marriages to ‘West Indian’ heiresses, investment in the South Sea Bubble, or involvement (on either side of the debate) in the Parliamentary process which led to abolition. This was an initial survey of the secondary literature and various databases, including one detailing the individuals who were paid reparations for the loss of their enslaved ‘property’ in 1834. Further examination of house archives, furnishings and architecture would provide further or new evidence of these connections. This is a story that needs to be told in full, for all the houses in this country, whether they are cared for by English Heritage, the National Trust or private owners. Then, in 2033, we will be better able to commemorate the Abolition of Slavery, as opposed to the Slave Trade. We will also be better equipped to make informed judgements on the issues that arise. more

Encyclopaedia of Blacks in European History and Culture , ed. E.Martone (2 vols., 2008).

‘Courts, Blacks at Early Modern European Aristocratic’ (Vol. I, pp. 163-166)

People of African origin or descent were present at most European royal and aristocratic courts during the early modern period, where they performed a variety of roles ranging from stable hand to prince. Africans had long been part of court culture, but numbers increased as a result of European involvement in the slave trade to the Americas from the fifteenth century onward. Africans were not only a source of cheap labour, but also functioned as exotic symbols of power and wealth. more

'English Common Law, Slavery and' (Vol. I, pp. 200-203)

No statutes codifying modern slavery were ever passed in England. The only forced labor recognized in English law was feudal villeinage, which had died out by the seventeenth century. Confusion arose when Englishmen began to bring blacks they had legally bought as slaves in the colonies back to England. The colonial legislatures had laws to define slave status, but English law did not. From the precedents created by a series of cases that came before English Law courts regarding slavery, we must conclude that the status of slaves under English law remained ambiguous, despite the famous decision in the Somerset Case in 1772, until slavery was finally abolished in the British Empire by Parliamentary statute on August 28, 1833. more

‘Prester John’ (Vol. II, pp.423-424)Prester John was a mythical figure, who from the twelfth to seventeenth centuries, was thought by Europeans to be a real personage, ruling over a distant Christian empire, originally located in Asia, but from 1300 onwards increasingly associated with Ethiopia. Europeans wanted to believe in the universality of Christianity and in a potential ally in their struggle against the Muslim powers. more

‘Somersett Case’ (Vol. II, pp.504-505) In the Somerset case of 1772, William Murray, Lord Chief Justice Mansfield, ruled that it was unlawful for Charles Stewart, a Boston, Massachussets, customs official, to transport James Somerset, an African he had bought in Virginia, forcibly out of England. The decision was popularly taken to mean that slavery was illegal in England, but Mansfield had only meant to give a narrow judgement, and even that was not enforced. more

People of African origin or descent were present at most European royal and aristocratic courts during the early modern period, where they performed a variety of roles ranging from stable hand to prince. Africans had long been part of court culture, but numbers increased as a result of European involvement in the slave trade to the Americas from the fifteenth century onward. Africans were not only a source of cheap labour, but also functioned as exotic symbols of power and wealth. more

'English Common Law, Slavery and' (Vol. I, pp. 200-203)

No statutes codifying modern slavery were ever passed in England. The only forced labor recognized in English law was feudal villeinage, which had died out by the seventeenth century. Confusion arose when Englishmen began to bring blacks they had legally bought as slaves in the colonies back to England. The colonial legislatures had laws to define slave status, but English law did not. From the precedents created by a series of cases that came before English Law courts regarding slavery, we must conclude that the status of slaves under English law remained ambiguous, despite the famous decision in the Somerset Case in 1772, until slavery was finally abolished in the British Empire by Parliamentary statute on August 28, 1833. more

‘Prester John’ (Vol. II, pp.423-424)Prester John was a mythical figure, who from the twelfth to seventeenth centuries, was thought by Europeans to be a real personage, ruling over a distant Christian empire, originally located in Asia, but from 1300 onwards increasingly associated with Ethiopia. Europeans wanted to believe in the universality of Christianity and in a potential ally in their struggle against the Muslim powers. more

‘Somersett Case’ (Vol. II, pp.504-505) In the Somerset case of 1772, William Murray, Lord Chief Justice Mansfield, ruled that it was unlawful for Charles Stewart, a Boston, Massachussets, customs official, to transport James Somerset, an African he had bought in Virginia, forcibly out of England. The decision was popularly taken to mean that slavery was illegal in England, but Mansfield had only meant to give a narrow judgement, and even that was not enforced. more

The Oxford Companion to Black British History, eds. D. Dabydeen, J. Gilmore and C. Jones (2007).

‘Dunbar, Rudolph (1899-1988)', pp.135-136.

Classical musician and war correspondent born in British Guiana (now Guyana). Dunbar began his musical career with the British Guianan militia band. He moved to New York at the age of 20, where he studied music at Columbia University. In 1925 he moved to Paris, where he studied music, journalism and philosophy. By 1931, he had settled in London and founded the Rudolph Dunbar School of Clarinet Playing. The same year, Melody Maker invited him to contribute a series of articles on the clarinet. These were successful enough for him to publish in 1939 A Treatise on the Clarinet (Boehm System). Dunbar was a successful conductor, especially in the 1940s, when he became the first black man to conduct an orchestra in many of the major cities of Europe, including, in 1942, the London Philharmonic at the Albert Hall, to an audience of 7,000 people; the Berlin Philharmonic (1945), and in 1948 at the Hollywood Bowl.

Dunbar was also a journalist. In 1932, he had become the London correspondent of the Associated Negro Press, reporting for them on the debates in the House of Commons in 1936 on the Italian invasion of Ethiopia. He served as a war correspondent with the American 8th Army, and crossed the Channel on D Day. He distinguished himself by warning the US 969th battalion of an ambush near Marchin during the Battle of the Bulge.

Despite appearances on the BBC in 1940 and 1941, his post-war musical career declined. He continued to teach and encourage younger musicians, but he grew introspective, believing his racial origins thwarted his progress. Dunbar died, unmarried, of cancer in 1988.

‘Golliwog’, pp.191-2.

A black-faced, shock-haired, fat red lipped and goggled-eyed character in brightly coloured clothes introduced to Britain in 1895 with the publication of Bertha and Florence Kate Upton’s The Adventures of Two Dutch Dolls. Such was the popularity of the central Golliwog’s character that the Uptons produced twelve sequels until 1909, which were reprinted many times until the late 1970s. The character was brave, courteous and loveable ‘the prince of golliwogs’, based on a black faced minstrel doll Upton had had as a child in America. During the First World War she put the original manuscripts and toys up for auction, raising £472 10s. which purchased an ambulance called the Golliwog for the Red Cross. The buyer presented the items to the Prime Minister, and they lived at Chequers for some 90 years before being recently moved to the Museum of Childhood in Bethnal Green.

As neither the Uptons nor Helen Bannerman, creator of Little Black Sambo, filed for copyright, British manufacturers, writers, and artists were free to adopt the character as their own. The earliest golliwog doll was sold at Gamages department store in 1902. Golliwogs were to be found everywhere from postcards to the sixth movement of Claude Debussy’s Children’s Corner, entitled ‘Golliwogg’s Cakewalk’. more

‘Tudor Britain’, pp.486-7.

From the early years of the 16th century there were Africans at both the Tudor and Stuart Courts. Catherine of Aragon had brought some African attendants with her when she arrived to marry Prince Arthur in 1501. One of these was the trumpeter ironically named John Blanke (blanco, white), who was paid 8d. a day for his services and was depicted twice in the Great Tournament Roll of Westminster (1511). In 1523 it is recorded that Fraunces Negro was working in the Queen’s stables. At the Court of James IV of Scotland, Africans first arrived as booty from a Prtuguese ship seized by the Barton brothers, and from 1500 to 1504 Peter the More served the Scottish King. Living at court at this time were a ‘More taubronar’, or drummer, with his wife and child and two maids known as ‘blak Margaret’ and ‘blak Elene’. One of these ‘More lassis’ was baptised on 11 December 1504. In 1505-6 King James tipped a nurse 28s. for bringing a ‘Moris barne’ to see him. more

Classical musician and war correspondent born in British Guiana (now Guyana). Dunbar began his musical career with the British Guianan militia band. He moved to New York at the age of 20, where he studied music at Columbia University. In 1925 he moved to Paris, where he studied music, journalism and philosophy. By 1931, he had settled in London and founded the Rudolph Dunbar School of Clarinet Playing. The same year, Melody Maker invited him to contribute a series of articles on the clarinet. These were successful enough for him to publish in 1939 A Treatise on the Clarinet (Boehm System). Dunbar was a successful conductor, especially in the 1940s, when he became the first black man to conduct an orchestra in many of the major cities of Europe, including, in 1942, the London Philharmonic at the Albert Hall, to an audience of 7,000 people; the Berlin Philharmonic (1945), and in 1948 at the Hollywood Bowl.

Dunbar was also a journalist. In 1932, he had become the London correspondent of the Associated Negro Press, reporting for them on the debates in the House of Commons in 1936 on the Italian invasion of Ethiopia. He served as a war correspondent with the American 8th Army, and crossed the Channel on D Day. He distinguished himself by warning the US 969th battalion of an ambush near Marchin during the Battle of the Bulge.

Despite appearances on the BBC in 1940 and 1941, his post-war musical career declined. He continued to teach and encourage younger musicians, but he grew introspective, believing his racial origins thwarted his progress. Dunbar died, unmarried, of cancer in 1988.

‘Golliwog’, pp.191-2.

A black-faced, shock-haired, fat red lipped and goggled-eyed character in brightly coloured clothes introduced to Britain in 1895 with the publication of Bertha and Florence Kate Upton’s The Adventures of Two Dutch Dolls. Such was the popularity of the central Golliwog’s character that the Uptons produced twelve sequels until 1909, which were reprinted many times until the late 1970s. The character was brave, courteous and loveable ‘the prince of golliwogs’, based on a black faced minstrel doll Upton had had as a child in America. During the First World War she put the original manuscripts and toys up for auction, raising £472 10s. which purchased an ambulance called the Golliwog for the Red Cross. The buyer presented the items to the Prime Minister, and they lived at Chequers for some 90 years before being recently moved to the Museum of Childhood in Bethnal Green.

As neither the Uptons nor Helen Bannerman, creator of Little Black Sambo, filed for copyright, British manufacturers, writers, and artists were free to adopt the character as their own. The earliest golliwog doll was sold at Gamages department store in 1902. Golliwogs were to be found everywhere from postcards to the sixth movement of Claude Debussy’s Children’s Corner, entitled ‘Golliwogg’s Cakewalk’. more

‘Tudor Britain’, pp.486-7.

From the early years of the 16th century there were Africans at both the Tudor and Stuart Courts. Catherine of Aragon had brought some African attendants with her when she arrived to marry Prince Arthur in 1501. One of these was the trumpeter ironically named John Blanke (blanco, white), who was paid 8d. a day for his services and was depicted twice in the Great Tournament Roll of Westminster (1511). In 1523 it is recorded that Fraunces Negro was working in the Queen’s stables. At the Court of James IV of Scotland, Africans first arrived as booty from a Prtuguese ship seized by the Barton brothers, and from 1500 to 1504 Peter the More served the Scottish King. Living at court at this time were a ‘More taubronar’, or drummer, with his wife and child and two maids known as ‘blak Margaret’ and ‘blak Elene’. One of these ‘More lassis’ was baptised on 11 December 1504. In 1505-6 King James tipped a nurse 28s. for bringing a ‘Moris barne’ to see him. more

Was James VI simply playing the fool?, Notes and Queries, The Guardian, 22 September 2004, G2, p. 18.

Why was James VI of Scotland (I of England) dubbed the wisest fool in Christendom by Henry IV of France? Was this name given before, or after, the Union of the Crowns 1603?

The observation was first published in England by Sir Anthony Weldon in his The Court and Character of King James in 1650 (during the interregnum when such sentiments passed the censor). Weldon hated James, who expelled him from court in 1625. He wrote: "He was very crafty and cunning in petty things... inasmuch as a very wise man was wont to say, he believed him the very wisest fool in Christendom."

It is uncertain whether this "very wise man" was the Duc de Sully, Henri IV's finance minister, and close friend and battle companion, or the King of France himself. The original appraisal is most likely to date from 1603, when Henri sent Sully as an ambassador to England on James' accession. Sully would then have reported his impressions of the new king, resulting in an exchange such as: "Sire, the king of England is a fool." "In that case Sully, he is the wisest fool in Christendom." In any case, it cannot be later than 1610, when Henri IV was assassinated, and I imagine that Henri was too busy 1589-98 fighting the Catholic League for his right to the throne to consider James.

The oxymoronic jibe suggests that though James was extremely learned, and a published author, in the practice of rulership he could be extremely foolish. But perhaps this foolishness was a mask. Weldon wrote that James's private motto was "Qui nescit dissumulare, nescit regnare" (He who does not know how to dissimulate does not know how to reign). Perhaps James, like Hamlet, was merely putting on an antic disposition- playing the fool for his own purposes.