‘Courts, Blacks at Early Modern European Aristocratic’, Encyclopaedia of Blacks in European History and Culture (2008),Vol. I, pp. 163-166.

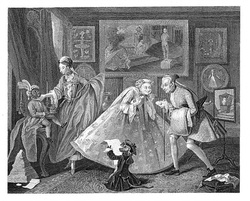

William Hogarth's Taste in High Life (1746)

People of African origin or descent were present at most European royal and aristocratic courts during the early modern period, where they performed a variety of roles ranging from stable hand to prince. Africans had long been part of court culture, but numbers increased as a result of European involvement in the slave trade to the Americas from the fifteenth century onward. Africans were not only a source of cheap labour, but also functioned as exotic symbols of power and wealth.

Europeans had employed black musicians and entertainers at court since at least 1194, when Holy Roman Emperor Henry VI (1165-1197) was accompanied by turbaned black trumpeters on his triumphal entry into Sicily. In 1470 a “black slave called Martino” was purchased to be the trumpeter on board the Neopolitan royal ship Barcha. Henry VII of England employed a black trumpeter named John Blanke, who was paid 8d a day in 1507. Henry VIII retained Blanke’s services. The Westminster Tournament Roll of 1511, which commemorates the celebrations that marked the birth of a short-lived son to Henry VIII and Katharine of Aragon, depicts a black trumpeter believed to be Blanke.

Elizabeth I had a “Lytle black a more” boy at her court and Anthonie Vause, a black trumpeter, was employed at the Tower of London in 1618. A Moorish “taubronar” or drummer devised a dance with 12 performers in black and white costumes for the Shrove Tuesday celebrations at the court of James IV of Scotland (1473-1513) in 1505. Teodosio I, Duke of Bragança (1510-1563) had ten black musicians, who played the charamela (a wind-instrument). A 1555 list of galley slaves belonging to Cosimo I de’ Medici (1519-1574) of Florence included a moro negro described as a trumpeter. In 1713, Frederick William I, later king of Prussia, asked for “several black boys aged between 13 and 15, all well-shaped” to be trained as musicians for his military regiments.

Blacks were often employed in royal and aristocratic stables. In 1507 the Duke of Medina Sidonia had seven black slaves working in his stables in Seville. Don Antonio, Prior of Crato (1531-1595) had a Moor named Antonio Luis working in his stable in Evora, brought from Tangiers, where he had been governor. Teodosio I of Bragança had 20 black stable boys. Blacks are often depicted handling horses in portraits, such as Daniel Mytens, King Charles and Queen Henrietta Maria Departing for the Chase (c.1630-32). Blacks were often excellent horsemen, such as the ‘Mour’ described in a letter from Lady Home to Mary of Guise in 1549 as being “as scharp a man as rydis.”

Blacks were also employed in the kitchen. King Joao III (1502-1557) gave his bride Catherine of Austria (1507-1578) a black pastry chef and confectioner named Domingos de Frorenca as a wedding present in 1526. They also had a black cook named Manuel. ‘James the Blackamoor’ was cook in the household of the Earl of Bath in Devon from 1639 to 1646.

The wealthiest aristocrats had the largest numbers of black slaves. Cardinal Luigi d’Este (1538-1586) had 80 slaves in his villa at Tivoli outside Rome. When they rebelled in 1580, he bought another 50. Teodosio I of Bragança owned 36 slaves: the Bragança were the most powerful noble family in Portugal, and eventually became her kings in the seventeenth century. Catherine of Austria, queen of Portugal from 1526 to 1557, was granted a yearly number of slaves from the customs houses. There were several blacks at the court of Louis XIV (1643-1715), including one presented to Queen Marie Therese in 1663. In 1680 Frederick William of Brandenberg established a Prussian outpost on the Gold Coast so that he could adorn his court with a few ‘handsome and well-built’ African men.

As a further display of wealth, black attendants were decked in rich clothes and jewellery. In 1577, Elizabeth I of England bought a “Garcon coate of white Taffeta, cut and lined with tincel, striped down with gold and silver…pointed with pynts and ribands” for her “lytle Blackamore.” In 1491 Isabella D’Este asked Giorgio Brognolo, her agent in Venice, to obtain “una moreta” between 1 ½ and 4 years old, and “as black as possible”. Darker skin was preferred, for it contrasted effectually with the diamond or pearl earrings with which the Africans would be adorned. It also set off the fair skin so prized by aristocratic women as depicted in portraits, where it was increasingly fashionable for a lady to be shown with a black attendant.

Some blacks took advantage of the opportunities available at court to advance themselves, either through education or military pursuits. João de Sa Panasco (fl.1524-1567), who began as a court jester in Lisbon, went on to become a gentleman of the household, king’s valet, a soldier who participated in Charles V’s campaign in North Africa in 1535 and finally member of the prestigious Order of Santiago. The Moor depicted by Jan Mostaert in a portrait (c.1525-30) seems to have reached a high status at the court of Margaret of Austria at Malines. The famous scholar Juan Latino (d.1590) grew up in the household of the Duke of Sessa in Granada, where he accompanied his young master to daily grammar classes, and eventually became a published author and lecturer at the University of Granada. Anton Wilhelm Amo, baptised in 1707 at Salzthal Castle, the home of the Duke of Wolfenbuttel, was to become a philosopher, with degrees from Universities of Halle and Wittenberg. Abraham Hannibal came to the court of Tsar Peter I (1672-1725) in Moscow in 1705 having been purchased by the Russian ambassador in Istanbul. He became a military engineer and major general. His great-grandson was Alexander Pushkin.

Not all blacks at European courts were purchased slaves. Visitors and ambassadors from Ethiopia and Congo were not uncommon. In 1488, Senegalese Prince “Bemoim” visited King Joao II in Lisbon. In 1491, Ercole d’Este of Ferrara began the practice of washing the feet of “religiosi indiani”, which were probably Ethiopian monks on their way to Rome as pilgrims. Some “blak More freirs” or friars were James IV’s guests at the Scottish court in 1508. In 1544 Dom Henrique, nephew of the King of Congo, visited Lisbon. Pope Leo X later consecrated him as a Bishop. A Morrocan embassy visited England in 1600. From 1652 to 1658, Abba Gregoryus, an Ethiopian priest, stayed at the court of Ernest, Duke of Saxony in Saxe-Gotha, where he tutored German scholar Job Lludolf in the languages of Ge’ez and Amharic.

One man of African descent actually ruled an early modern court. Alessandro de’Medici (1510-1537), the illegitimate son of a black woman, Simonetta da Colle Vecchio, became the first hereditary duke of Florence. Many European Royal Houses can trace their descent back to him.

(names in bold also have entries in the Encyclopaedia).

Europeans had employed black musicians and entertainers at court since at least 1194, when Holy Roman Emperor Henry VI (1165-1197) was accompanied by turbaned black trumpeters on his triumphal entry into Sicily. In 1470 a “black slave called Martino” was purchased to be the trumpeter on board the Neopolitan royal ship Barcha. Henry VII of England employed a black trumpeter named John Blanke, who was paid 8d a day in 1507. Henry VIII retained Blanke’s services. The Westminster Tournament Roll of 1511, which commemorates the celebrations that marked the birth of a short-lived son to Henry VIII and Katharine of Aragon, depicts a black trumpeter believed to be Blanke.

Elizabeth I had a “Lytle black a more” boy at her court and Anthonie Vause, a black trumpeter, was employed at the Tower of London in 1618. A Moorish “taubronar” or drummer devised a dance with 12 performers in black and white costumes for the Shrove Tuesday celebrations at the court of James IV of Scotland (1473-1513) in 1505. Teodosio I, Duke of Bragança (1510-1563) had ten black musicians, who played the charamela (a wind-instrument). A 1555 list of galley slaves belonging to Cosimo I de’ Medici (1519-1574) of Florence included a moro negro described as a trumpeter. In 1713, Frederick William I, later king of Prussia, asked for “several black boys aged between 13 and 15, all well-shaped” to be trained as musicians for his military regiments.

Blacks were often employed in royal and aristocratic stables. In 1507 the Duke of Medina Sidonia had seven black slaves working in his stables in Seville. Don Antonio, Prior of Crato (1531-1595) had a Moor named Antonio Luis working in his stable in Evora, brought from Tangiers, where he had been governor. Teodosio I of Bragança had 20 black stable boys. Blacks are often depicted handling horses in portraits, such as Daniel Mytens, King Charles and Queen Henrietta Maria Departing for the Chase (c.1630-32). Blacks were often excellent horsemen, such as the ‘Mour’ described in a letter from Lady Home to Mary of Guise in 1549 as being “as scharp a man as rydis.”

Blacks were also employed in the kitchen. King Joao III (1502-1557) gave his bride Catherine of Austria (1507-1578) a black pastry chef and confectioner named Domingos de Frorenca as a wedding present in 1526. They also had a black cook named Manuel. ‘James the Blackamoor’ was cook in the household of the Earl of Bath in Devon from 1639 to 1646.

The wealthiest aristocrats had the largest numbers of black slaves. Cardinal Luigi d’Este (1538-1586) had 80 slaves in his villa at Tivoli outside Rome. When they rebelled in 1580, he bought another 50. Teodosio I of Bragança owned 36 slaves: the Bragança were the most powerful noble family in Portugal, and eventually became her kings in the seventeenth century. Catherine of Austria, queen of Portugal from 1526 to 1557, was granted a yearly number of slaves from the customs houses. There were several blacks at the court of Louis XIV (1643-1715), including one presented to Queen Marie Therese in 1663. In 1680 Frederick William of Brandenberg established a Prussian outpost on the Gold Coast so that he could adorn his court with a few ‘handsome and well-built’ African men.

As a further display of wealth, black attendants were decked in rich clothes and jewellery. In 1577, Elizabeth I of England bought a “Garcon coate of white Taffeta, cut and lined with tincel, striped down with gold and silver…pointed with pynts and ribands” for her “lytle Blackamore.” In 1491 Isabella D’Este asked Giorgio Brognolo, her agent in Venice, to obtain “una moreta” between 1 ½ and 4 years old, and “as black as possible”. Darker skin was preferred, for it contrasted effectually with the diamond or pearl earrings with which the Africans would be adorned. It also set off the fair skin so prized by aristocratic women as depicted in portraits, where it was increasingly fashionable for a lady to be shown with a black attendant.

Some blacks took advantage of the opportunities available at court to advance themselves, either through education or military pursuits. João de Sa Panasco (fl.1524-1567), who began as a court jester in Lisbon, went on to become a gentleman of the household, king’s valet, a soldier who participated in Charles V’s campaign in North Africa in 1535 and finally member of the prestigious Order of Santiago. The Moor depicted by Jan Mostaert in a portrait (c.1525-30) seems to have reached a high status at the court of Margaret of Austria at Malines. The famous scholar Juan Latino (d.1590) grew up in the household of the Duke of Sessa in Granada, where he accompanied his young master to daily grammar classes, and eventually became a published author and lecturer at the University of Granada. Anton Wilhelm Amo, baptised in 1707 at Salzthal Castle, the home of the Duke of Wolfenbuttel, was to become a philosopher, with degrees from Universities of Halle and Wittenberg. Abraham Hannibal came to the court of Tsar Peter I (1672-1725) in Moscow in 1705 having been purchased by the Russian ambassador in Istanbul. He became a military engineer and major general. His great-grandson was Alexander Pushkin.

Not all blacks at European courts were purchased slaves. Visitors and ambassadors from Ethiopia and Congo were not uncommon. In 1488, Senegalese Prince “Bemoim” visited King Joao II in Lisbon. In 1491, Ercole d’Este of Ferrara began the practice of washing the feet of “religiosi indiani”, which were probably Ethiopian monks on their way to Rome as pilgrims. Some “blak More freirs” or friars were James IV’s guests at the Scottish court in 1508. In 1544 Dom Henrique, nephew of the King of Congo, visited Lisbon. Pope Leo X later consecrated him as a Bishop. A Morrocan embassy visited England in 1600. From 1652 to 1658, Abba Gregoryus, an Ethiopian priest, stayed at the court of Ernest, Duke of Saxony in Saxe-Gotha, where he tutored German scholar Job Lludolf in the languages of Ge’ez and Amharic.

One man of African descent actually ruled an early modern court. Alessandro de’Medici (1510-1537), the illegitimate son of a black woman, Simonetta da Colle Vecchio, became the first hereditary duke of Florence. Many European Royal Houses can trace their descent back to him.

(names in bold also have entries in the Encyclopaedia).