Africans in early modern London: Tales from London Metropolitan Archives (LMA), 25 July 2012.

Miranda Kaufmann shares some of the stories she has uncovered whilst researching her Oxford D.Phil thesis on ‘Africans in Britain, 1500-1640’.

In September 1615, a Ratcliffe mariner named Thomas Jeronimo, his wife Helen and a musician named John Anthony all appeared at the Middlesex Quarter Sessions. Helen was suspected of stealing ‘14 bookes of callikoe, 26 pieces of pachers and 108 lb. of suger’ from a merchant named Francis Pinto. Both men were described as ‘Maurus’ - meaning ‘moor’. (LMA MJ/SR/S53, nos. 112, 113; British History Online.)

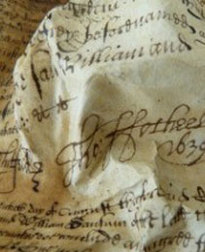

Unfortunately, no further details of this case survive. It is one of many tantalising glimpses of the lives of Africans in early modern London that can be found in the records held at London Metropolitan Archives (LMA). The majority of the evidence comes from the parish registers, where the baptisms, marriages and burials of Africans were recorded. The Black and Asian Londoners Project, which ran from 2001 until 2003 at LMA, found over 2,000 references to Black or Asian Londoners in the baptism registers of the ancient parishes of London and Middlesex between 1597 and 1856. Since most of the records previously held at Guildhall Library have been transferred to LMA, the visitor also now has access to the entries from the City of London parishes which are being searched from 1538-1837 in a partner project (still on-going), many of which have been transcribed here. A gem of this collection is the parish register of St. Botolph Aldgate, whose clerk, Thomas Harridance, gave unusually detailed descriptions, such as that of the baptism of Mary Phyllis on 3 June 1597. LMA also holds microfilms of the Bridewell Court Books, which contain some colourful snippets, such as the presentment in March 1628 of ‘Peter Cavandigoe...a Blackmore for being an idle and wandring p[er]son and for breaking a boyes leg with a broome staffe as the boy past along street not giving him any cause of offence’. (CLC/275/MS/33011/007 f.65v.)

Many more stories like this must lurk in the archives. However, they are not easy to find. Much of the source material for this period remains unprinted, unedited and un-indexed. Further, indexes of surnames or even places are not much use when looking for Africans. The 2001-3 Black and Asian Londoner’s Project worked systematically through the baptism records, but no similarly thorough search has yet been made of marriage or burial registers for the ancient parishes of London and Middlesex. The City of London parishes are being searched for baptisms, marriages and burials, and although there are few marriages, there are twice as many known burials as baptism records of Africans suggesting that going through the London and Middlesex burials would be a fruitful future project.

The great advance that is beginning to make uncovering the early black population of London less laborious is the digitisation of primary material and calendars. An increasing number of sources are available online, vitally with full text searches. Initiatives such as State Papers Online and British History Online make it possible for the first time to search a huge number of texts for contemporary key words such as ‘blackamoor’ or ‘negro’.

In fact it was by searching for ‘moor’ on British History Online that I first came across the Jeronimo case. I was also able to find out a little more about Helen and Thomas, when I found them mentioned in some petitions to the East India Company in 1623-4, now held in the British Library. By November 1623, Helen Jeronimo was a penniless widow, and is in this record described as a ‘moore’ (this important detail was not mentioned in 1615). The East India Company’s Court Minute Book records that because she was ‘a stranger... haveing few friends and her husband lost the Court was contented to relieve her with xx[20] s out of the poores boxe which she thankfully accepted.’(BL, IOR/574, B8: Court Minute Book VI, f. 280.) The following year she received a further 10 shillings and we learn that her husband Thomas died at sea in a ship called the Peppercorne, which had sailed to the Philippines, and had received £16 16s 10d from the East India Company for his services. (BL, IOR/575, B/9: Court Minute Book VII, f. 78.)

Interestingly, this was not the only married black couple in London at this time. The Jeronimos lived in Ratcliffe, and there were three marriages between black partners recorded at the nearby church of St. Dunstan and All Saints, Stepney between 1608 and 1610. In July 1608 ‘Peter & Mary both nigers’ were married. The following February saw the nuptials of ‘John Mens of Ratclif a niger & Luce Pluatt a niger’, and in September 1610, ‘Salomon Cowrder of Popler a niger sailler & Katheren Castilliano a niger also’ were united. Another similar marriage is suggested in the 1618 burial record at St. Botolph Aldgate of ‘Anne Vause, a black-more, wife to Anthonie Vause, Trompetter, of the said countrey’. (P69/BOT2/A/015/MS09222/001.) As no other country is referred to in the immediate proximity of this record, it seems fair to conclude that Anthony is of the same country as his wife. It is also interesting to note that Salomon Cowrdrer of Poplar was also a sailor, who ‘came out of the East Indies’, which may mean the term ‘niger’ is being used loosely, describing a native of Asia rather than Africa, or was one of those Africans taken to the East Indies by the Portuguese, and later the Dutch, or that Cowrder was last employed on a ship that had sailed to the East Indies, like Thomas Jeronimo.

As we might guess from the nature of the goods Helen allegedly stole from him, the converso (Portuguese Jewish) merchant Francis Pinto also appears in the annals of the East India Company. Born in Lisbon, he had lived in Oporto and Amsterdam before coming to London around 1608, where he died in 1618. What is more interesting is that the parish register of St Olave, Hart Street records that ‘the blackamore gerl from Mr.Pintoes’ was buried on 14 March 1611. (P69/OLA1/A/001/MS28867.) Pinto was not the only Portuguese exile to have African servants in his household. But that’s another story.

In September 1615, a Ratcliffe mariner named Thomas Jeronimo, his wife Helen and a musician named John Anthony all appeared at the Middlesex Quarter Sessions. Helen was suspected of stealing ‘14 bookes of callikoe, 26 pieces of pachers and 108 lb. of suger’ from a merchant named Francis Pinto. Both men were described as ‘Maurus’ - meaning ‘moor’. (LMA MJ/SR/S53, nos. 112, 113; British History Online.)

Unfortunately, no further details of this case survive. It is one of many tantalising glimpses of the lives of Africans in early modern London that can be found in the records held at London Metropolitan Archives (LMA). The majority of the evidence comes from the parish registers, where the baptisms, marriages and burials of Africans were recorded. The Black and Asian Londoners Project, which ran from 2001 until 2003 at LMA, found over 2,000 references to Black or Asian Londoners in the baptism registers of the ancient parishes of London and Middlesex between 1597 and 1856. Since most of the records previously held at Guildhall Library have been transferred to LMA, the visitor also now has access to the entries from the City of London parishes which are being searched from 1538-1837 in a partner project (still on-going), many of which have been transcribed here. A gem of this collection is the parish register of St. Botolph Aldgate, whose clerk, Thomas Harridance, gave unusually detailed descriptions, such as that of the baptism of Mary Phyllis on 3 June 1597. LMA also holds microfilms of the Bridewell Court Books, which contain some colourful snippets, such as the presentment in March 1628 of ‘Peter Cavandigoe...a Blackmore for being an idle and wandring p[er]son and for breaking a boyes leg with a broome staffe as the boy past along street not giving him any cause of offence’. (CLC/275/MS/33011/007 f.65v.)

Many more stories like this must lurk in the archives. However, they are not easy to find. Much of the source material for this period remains unprinted, unedited and un-indexed. Further, indexes of surnames or even places are not much use when looking for Africans. The 2001-3 Black and Asian Londoner’s Project worked systematically through the baptism records, but no similarly thorough search has yet been made of marriage or burial registers for the ancient parishes of London and Middlesex. The City of London parishes are being searched for baptisms, marriages and burials, and although there are few marriages, there are twice as many known burials as baptism records of Africans suggesting that going through the London and Middlesex burials would be a fruitful future project.

The great advance that is beginning to make uncovering the early black population of London less laborious is the digitisation of primary material and calendars. An increasing number of sources are available online, vitally with full text searches. Initiatives such as State Papers Online and British History Online make it possible for the first time to search a huge number of texts for contemporary key words such as ‘blackamoor’ or ‘negro’.

In fact it was by searching for ‘moor’ on British History Online that I first came across the Jeronimo case. I was also able to find out a little more about Helen and Thomas, when I found them mentioned in some petitions to the East India Company in 1623-4, now held in the British Library. By November 1623, Helen Jeronimo was a penniless widow, and is in this record described as a ‘moore’ (this important detail was not mentioned in 1615). The East India Company’s Court Minute Book records that because she was ‘a stranger... haveing few friends and her husband lost the Court was contented to relieve her with xx[20] s out of the poores boxe which she thankfully accepted.’(BL, IOR/574, B8: Court Minute Book VI, f. 280.) The following year she received a further 10 shillings and we learn that her husband Thomas died at sea in a ship called the Peppercorne, which had sailed to the Philippines, and had received £16 16s 10d from the East India Company for his services. (BL, IOR/575, B/9: Court Minute Book VII, f. 78.)

Interestingly, this was not the only married black couple in London at this time. The Jeronimos lived in Ratcliffe, and there were three marriages between black partners recorded at the nearby church of St. Dunstan and All Saints, Stepney between 1608 and 1610. In July 1608 ‘Peter & Mary both nigers’ were married. The following February saw the nuptials of ‘John Mens of Ratclif a niger & Luce Pluatt a niger’, and in September 1610, ‘Salomon Cowrder of Popler a niger sailler & Katheren Castilliano a niger also’ were united. Another similar marriage is suggested in the 1618 burial record at St. Botolph Aldgate of ‘Anne Vause, a black-more, wife to Anthonie Vause, Trompetter, of the said countrey’. (P69/BOT2/A/015/MS09222/001.) As no other country is referred to in the immediate proximity of this record, it seems fair to conclude that Anthony is of the same country as his wife. It is also interesting to note that Salomon Cowrdrer of Poplar was also a sailor, who ‘came out of the East Indies’, which may mean the term ‘niger’ is being used loosely, describing a native of Asia rather than Africa, or was one of those Africans taken to the East Indies by the Portuguese, and later the Dutch, or that Cowrder was last employed on a ship that had sailed to the East Indies, like Thomas Jeronimo.

As we might guess from the nature of the goods Helen allegedly stole from him, the converso (Portuguese Jewish) merchant Francis Pinto also appears in the annals of the East India Company. Born in Lisbon, he had lived in Oporto and Amsterdam before coming to London around 1608, where he died in 1618. What is more interesting is that the parish register of St Olave, Hart Street records that ‘the blackamore gerl from Mr.Pintoes’ was buried on 14 March 1611. (P69/OLA1/A/001/MS28867.) Pinto was not the only Portuguese exile to have African servants in his household. But that’s another story.