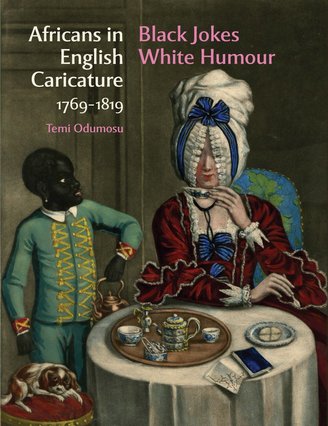

Temi Odumosu, BLACK JOKES, WHITE HUMOUR: AFRICANS IN ENGLISH CARICATURE, 1769–1819, Slavery & Abolition journal, Published online: 15 Nov 2018

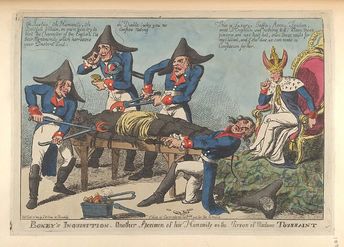

Boney’s Inquisition: Another Specimen of his Humanity on the Person of Madame Toussaint, 25 October 1804,

Boney’s Inquisition: Another Specimen of his Humanity on the Person of Madame Toussaint, 25 October 1804,

In Boney’s Inquisition: Another Specimen of his Humanity on the Person of Madame Toussaint, a hand-coloured etching published in London on 25 October 1804, Charles Williams draws Napoleon looking on as four of his henchmen squeeze the naked nipples of Suzanne Simone Baptiste L’Ouverture with red-hot pincers and pull off her fingernails with a pair of tongs. This gruesome image led Temi Odumosu to discover a letter published in the national paper Bell’s Weekly Messenger four days before the print. Penned by a Madame Bernard, widow of a Saint-Domingue planter now resident in New York, it detailed the gruesome torture the wife of the famous Haitian revolutionary had been subjected to before she managed to escape to America. After sessions in Bordeaux and Paris, Bernard relates that Suzanne had endured ‘the most excruciating pain’ and sustained no less than 44 wounds to her body. She lost the use of her left arm and ‘pieces of flesh have been torn from her breasts as if with hot irons, together with six nails off her toes.’ Worst of all, she suffered a miscarriage. Historians had previously assumed that ‘Madame Toussaint’ died in a French prison: this print, like so many others in this eye-opening book, opens a ‘fascinating window into history’, allowing us to see the past anew.

For this beautifully illustrated study of African figures in English caricature, Odumosu has painstakingly unearthed over 600 prints created during the 50-year period in which this art form was at its height. Many were previously unknown, unpublished, or even suppressed. The more familiar works, including examples by major satirists such as Gillray, Rowlandson, and both Cruikshanks, have rarely, if ever, been considered in this context. more

These images demonstrate the Black presence, not only in Georgian Britain, but in the British imagination. Odumosu’s analysis, picking up the story where David Dabydeen left it at the end of Hogarth’s Blacks 30 years ago, tracks the development of racist tropes and ideas as the period progresses. Many of the risqué, even titillating, scenes make for uncomfortable viewing, especially because, as Odumosu reminds us, we cannot distance ourselves from these images and the sometimes extreme examples of racism and misogynoir they represent. Golliwogs are still sold, black prostitutes are still exoticised, and most recently, tennis star Serena Williams was caricatured by Australian cartoonist Mark Knight in the same blatantly racist and misogynistic visual language used 200 years ago.

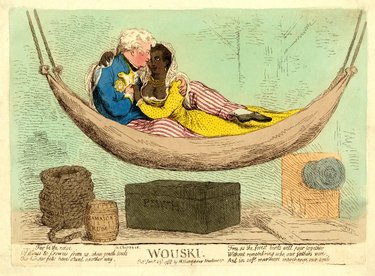

Racial stereotypes were, and are, highly gendered, as the structure of the book reflects. Two chapters focus largely on male figures: chapter one on black male servants, specifically the popular figure of Mungo (originally a character in Isaac Bickerstaff’s 1768 play The Padlock) and chapter four, an in-depth study of the figures depicted in George Cruikshank and Frederick Marryat’s The New Union Club (1819); and two on female figures: chapter two on the ‘sable mistress’ and chapter three on James Gillray’s Wowski (1788) – a formerly suppressed print that also takes its name from a theatrical character- depicting the future William IV embracing his black mistress in a ship’s hammock.

These images demonstrate the Black presence, not only in Georgian Britain, but in the British imagination. Odumosu’s analysis, picking up the story where David Dabydeen left it at the end of Hogarth’s Blacks 30 years ago, tracks the development of racist tropes and ideas as the period progresses. Many of the risqué, even titillating, scenes make for uncomfortable viewing, especially because, as Odumosu reminds us, we cannot distance ourselves from these images and the sometimes extreme examples of racism and misogynoir they represent. Golliwogs are still sold, black prostitutes are still exoticised, and most recently, tennis star Serena Williams was caricatured by Australian cartoonist Mark Knight in the same blatantly racist and misogynistic visual language used 200 years ago.

Racial stereotypes were, and are, highly gendered, as the structure of the book reflects. Two chapters focus largely on male figures: chapter one on black male servants, specifically the popular figure of Mungo (originally a character in Isaac Bickerstaff’s 1768 play The Padlock) and chapter four, an in-depth study of the figures depicted in George Cruikshank and Frederick Marryat’s The New Union Club (1819); and two on female figures: chapter two on the ‘sable mistress’ and chapter three on James Gillray’s Wowski (1788) – a formerly suppressed print that also takes its name from a theatrical character- depicting the future William IV embracing his black mistress in a ship’s hammock.

Gillray's Wowski, 1788.

Gillray's Wowski, 1788.

Odumosu excels in placing the prints in the context of the literary culture of the day, using plays, letters and newspaper reports to give a multifaceted account of the ways Africans were caricatured in this period. Her approach of looking at the history through the window of the prints allows us to glimpse many unexpected stories. Besides the horrific tortures of Suzanne L’Ouverture and Prince William’s scandalous affair, we learn of a fencing match between George Turner ‘a Moor’ and an Englishman in Southwark in 1710; that Richard Steele of Spectator fame was a plantation owner; that English portraitist Richard Evans served as court painter to King Henry Christophe of Haiti; and that Christophe’s widow and daughters were later hosted by the abolitionist Thomas Clarkson at his home in Ipswich.

The 50 years covered by the book were a hugely eventful period of Black British History, not only seeing the growth and eventual success of the abolitionist movement, but also witnessing a series of legal judgements, most famously in the Somerset and Knight vs. Wedderburn cases of the 1770s. Despite these rulings, the Scottish more emphatic than the English, the legal status of Africans in Britain remains a vexed question amongst historians. Odumosu does not fully engage with this debate, resorting to using the somewhat contradictory phrase ‘enslaved servant’. She often assumes that caricatured African figures were slaves: one man, innocently standing at the back of a crowd, has a ‘body [which] implies servitude’, others are ‘human property’, or non-entities ‘without rights, voice or agency’, whereas the research of Kathleen Chater and others has revealed many records of Africans in Britain living free lives: being paid wages, or working independently: a barrister, a cabinet-maker, a parish constable. The problem with peering through ‘fascinating windows into history’ is that the voyeur does not always see the whole picture. Sometimes, in her pursuit of caricatured figures, Odumosu loses sight of the real African men and women living in Georgian Britain. For example, she quotes Horace Walpole referring to the sisters of Lord Milford’s ‘favourite black’ in a letter, but never mentions that this man was none other than the Senegalese Caesar Picton, who, taking his name from their country seat of Picton Castle, Pembrokeshire, went on to become a successful coal merchant in Kingston, Surrey.

Nonetheless, in compiling and interrogating this extensive catalogue of visual evidence, Odumosu has performed a great feat of scholarship. These more rough and ready, more portable and thus more widely circulated images, give us a very different perspective to that gained from the more familiar oil paintings of wealthy men and women with black attendants. The number and quality of the illustrations alone make this book a significant contribution to the field. Being able to view them directly alongside the text allows the reader to consider and absorb Odumosu’s argument without constantly flicking pages or searching for larger images online. More importantly, her perceptive, fresh and scholarly analysis greatly enhances our understanding of Georgian attitudes to race and gender, and of the experience of the many Africans living in Georgian Britain.

The 50 years covered by the book were a hugely eventful period of Black British History, not only seeing the growth and eventual success of the abolitionist movement, but also witnessing a series of legal judgements, most famously in the Somerset and Knight vs. Wedderburn cases of the 1770s. Despite these rulings, the Scottish more emphatic than the English, the legal status of Africans in Britain remains a vexed question amongst historians. Odumosu does not fully engage with this debate, resorting to using the somewhat contradictory phrase ‘enslaved servant’. She often assumes that caricatured African figures were slaves: one man, innocently standing at the back of a crowd, has a ‘body [which] implies servitude’, others are ‘human property’, or non-entities ‘without rights, voice or agency’, whereas the research of Kathleen Chater and others has revealed many records of Africans in Britain living free lives: being paid wages, or working independently: a barrister, a cabinet-maker, a parish constable. The problem with peering through ‘fascinating windows into history’ is that the voyeur does not always see the whole picture. Sometimes, in her pursuit of caricatured figures, Odumosu loses sight of the real African men and women living in Georgian Britain. For example, she quotes Horace Walpole referring to the sisters of Lord Milford’s ‘favourite black’ in a letter, but never mentions that this man was none other than the Senegalese Caesar Picton, who, taking his name from their country seat of Picton Castle, Pembrokeshire, went on to become a successful coal merchant in Kingston, Surrey.

Nonetheless, in compiling and interrogating this extensive catalogue of visual evidence, Odumosu has performed a great feat of scholarship. These more rough and ready, more portable and thus more widely circulated images, give us a very different perspective to that gained from the more familiar oil paintings of wealthy men and women with black attendants. The number and quality of the illustrations alone make this book a significant contribution to the field. Being able to view them directly alongside the text allows the reader to consider and absorb Odumosu’s argument without constantly flicking pages or searching for larger images online. More importantly, her perceptive, fresh and scholarly analysis greatly enhances our understanding of Georgian attitudes to race and gender, and of the experience of the many Africans living in Georgian Britain.