"Based on a True Story"?

Like any historical film "Based on a True Story", Belle takes liberties with the historical record. Alex von Tunzelman has made a good start on sifting the fact from fiction in her Reel History column in the Guardian. You can find a brief biography of Dido in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Or read Paula Byrne's book for more background to the few details we have of Dido's life. You can read more about the legal history of slavery in England here. It's also worth paying a visit to Kenwood, especially if you take a look in the writing desk in the library, where you will find a brief pamphlet on " Lord Mansfield, Slavery and the Law", as well as reproductions of some of the original documents relating to Dido, including a letter she wrote on her great-uncle's behalf.

Dido's status

The film shows Dido as occupying a strange position in the hierarchy of the Kenwood household. She is part of the family, and yet may not dine with them. The historical source for this is an entry in the diary of one Thomas Hutchinson, the exiled Governor of Massachusetts, who visited Lord Mansfield one evening in August 1779. In fact, this entry provides us with much of the known details of Dido's life. Hutchinson was hardly an unbiased observer, and mostly refers to Dido as "a Black". Paula Byrne points out that perhaps Dido did not attend dinner that night in order to shelter her from this man, rather than the other way round. Either way, the fact that she did not attend dinner on 29th August 1779 does not necessarily mean that she never dined with the family.

The fact that Dido helped manage the dairy is not an indicator of lower status. It was considered a genteel occupation for a lady, and even the Duke of Wellington took an interest in it, sharing his recipe for butter with Louisa, Lady Mansfield.

However, Dido was not the wealthy heiress that the film portrays. Her father left his money to two of his other illegitimate children. However, by giving her financial independence, the film asks interesting questions of the interplay of class, race, and cash in determining status in 18th century society. Although Dido was not an heiress, it was not inconceivable for a woman of her colour to be so. Many men who fathered children with enslaved women made attempts to provide for them, as Daniel Livesay's research has shown. Perhaps the best-known example of this was Nathaniel Wells, the son of William Wells and his house-slave, Juggy, who was educated in England, inherited his father's St. Kitts estate in 1794, and bought Piercefield estate near Chepstow, Monmouthshire in 1802, going on to become a Justice of the Peace in 1806 and Sheriff of Monmouthshire in 1818.

Portraits of Africans

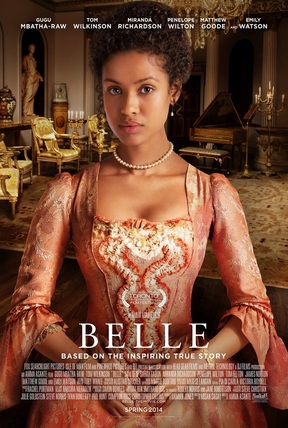

One of the fascinating threads of the film for me was the interaction between Belle, and the images of Africans she saw around her, both growing up at Kenwood, and around her in the streets of London. The film shows her as fearful of having her own portrait painted, lest she be portrayed in the subservient pose she assumes is the only way for people of her complexion to appear in art. While we have no idea what she felt about portraiture, the film dramatises a deeper truth. There are large numbers of the sort of pictures Belle despised hanging on the walls of country houses across Britain, including this one of Henrietta of Lorraine and her page by Van Dyck, now at Kenwood, and this portrait of Anne of Denmark and her groom, which I blogged about last year. However, there are also some fascinating portraits, besides Dido's, that give their black subjects dignity and character, such as Thomas Gainsborough's 1768 portrait of Ignatius Sancho. They key point about the portrait of Dido and her cousin, perhaps, is that it shows a black woman alongside a white woman in a position of relative equality.

I was pleased with the way the film brought to life the drama of the Zong case of 1783, but was amazed that it failed to make any mention of Lord Mansfield's earlier judgments regarding slavery, most pertinently, that in the Somerset case of 1772. I suppose the film-makers thought the audience could only deal with one monumental court case at a time! The script however, lifted the words Mansfield uttered in the Somerset case, on how slavery was odious, and placed them into his final judgment on the Zong.

African Extras

I was intrigued to see a large number of African men shown in the film as attending the final judgement in the Zong case. According to the IMDB, one of these is meant to be Olaudah Equiano, played by Lamin Tamba. Equiano actually played a pivotal role in the Zong drama, as it was he who alerted abolitionist Granville Sharp to the case's existence. Unfortunately, Dido does not speak to him, or the other well-dressed Africans she passes in the gallery, and so their stories remain untold. Her interaction with Mabel, the African maid is a little more detailed- and gives her the chance to ask Mansfield over breakfast: "Is Mabel a slave?" -This would have been an ideal opportunity for the Lord Chief Justice to explain the legal status of Africans in Britain, and his judgement in the Somerset case. Unfortunately, although we learn that Mabel is free, and paid wages, the subject is soon dismissed as not suitable for the breakfast table.

Other Stories to Tell...

As I told the Observer newspaper in January, I really hope that in the wake of 12 Years A Slave, and Belle, " film directors will turn their attention to telling Britain's slavery stories such as Equiano's which would help a new generation understand their nation's role in a trade referred to as 'the great circuit' and remind them that "Africans have been living in Britain for centuries before the Windrush". There are so many great stories still to tell. Maybe I should write a list of suggestions for up and coming filmmakers who want Oscar-winning material? But that's a blog for another day...

RSS Feed

RSS Feed