Marriage, Cherwell , Trinity 2005.

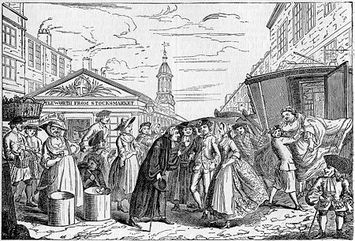

Fleet Street wedding.

In 1754 Lord Hardwicke’s Marriage Act was passed to prevent ‘both men and women of the most infamous character’ from ‘ruining the sons and daughters of the greatest families in England’. Due to ‘the convenience of marrying in the Fleet and other unlicensed places…marrying had become as much a trade as any mechanical profession’. A fortune could easily be made by marrying an heir or heiress.

It seems that early 18th century London was not unlike modern Las Vegas in its provision of quick and easy marriage, no questions asked. It was reported that ‘there’s such a coupling at Pancras that they stand behind one another as ‘twere in a country dance’ . Fleet Street flocked with touts asking ‘Sir, will you be pleased to walk in and be married?’. Unscrupulous clerics would happily backdate papers to legitimise children, or even supply a man for a woman needing a husband in a hurry- for a fee. Captain Basil in Farrquhar’s The Stage Coach recounts how one particularly accommodating parson, whom he and his wife-to-be found in his chamber, smoking his pipe, ‘first gave us his blessing, then lent us his bed’.

On 25th March 1754, the day before the implementation of the Act, 217 Fleet marriages were registered. After 1754, young couples had to flee to Gretna Green, just over the Scottish border for such services. In 1773, there was a complaint in the Lady’s Magazine that ‘no law was ever made since the Revolution that has occasioned so many broken hearts, unhappy lives and accumulated distresses as this has’.

The main reason that the act caused broken hearts was its stipulation that those aged under 21 were not allowed to marry without parental consent. The Act further confirmed that nothing other than a church wedding, announced (the banns read) three times in advance, entered in the parish register which was signed by both parties was legally binding.

Up until 1754, the English authorities had recognised another type of marriage: an oral promise to marry (known as spousals), uttered in front of witnesses. This was legally binding, especially if followed by consummation. Annulment could be granted on various grounds, including that of male impotence over three years, which late medieval courts tested by having the wife inspected by other women to establish whether her hymen was still intact, or by leaving the husband alone with seven women who would use their feminine wiles to ascertain if he were capable of getting an erection.

If such an inspection did not tempt him, a husband had recourse to an old folk custom: that of divorce by ‘wife-sale’. A described in 1727, the husband would ‘put a halter about her neck and thereby lead her to the next market place, and there put her up to auction to be sold to the best bidder as if she were a brood mare or milch-cow. A purchaser is generally provided beforehand on these occasions’. The last recorded case of ‘wife-sale’ was in 1887.

It seems that early 18th century London was not unlike modern Las Vegas in its provision of quick and easy marriage, no questions asked. It was reported that ‘there’s such a coupling at Pancras that they stand behind one another as ‘twere in a country dance’ . Fleet Street flocked with touts asking ‘Sir, will you be pleased to walk in and be married?’. Unscrupulous clerics would happily backdate papers to legitimise children, or even supply a man for a woman needing a husband in a hurry- for a fee. Captain Basil in Farrquhar’s The Stage Coach recounts how one particularly accommodating parson, whom he and his wife-to-be found in his chamber, smoking his pipe, ‘first gave us his blessing, then lent us his bed’.

On 25th March 1754, the day before the implementation of the Act, 217 Fleet marriages were registered. After 1754, young couples had to flee to Gretna Green, just over the Scottish border for such services. In 1773, there was a complaint in the Lady’s Magazine that ‘no law was ever made since the Revolution that has occasioned so many broken hearts, unhappy lives and accumulated distresses as this has’.

The main reason that the act caused broken hearts was its stipulation that those aged under 21 were not allowed to marry without parental consent. The Act further confirmed that nothing other than a church wedding, announced (the banns read) three times in advance, entered in the parish register which was signed by both parties was legally binding.

Up until 1754, the English authorities had recognised another type of marriage: an oral promise to marry (known as spousals), uttered in front of witnesses. This was legally binding, especially if followed by consummation. Annulment could be granted on various grounds, including that of male impotence over three years, which late medieval courts tested by having the wife inspected by other women to establish whether her hymen was still intact, or by leaving the husband alone with seven women who would use their feminine wiles to ascertain if he were capable of getting an erection.

If such an inspection did not tempt him, a husband had recourse to an old folk custom: that of divorce by ‘wife-sale’. A described in 1727, the husband would ‘put a halter about her neck and thereby lead her to the next market place, and there put her up to auction to be sold to the best bidder as if she were a brood mare or milch-cow. A purchaser is generally provided beforehand on these occasions’. The last recorded case of ‘wife-sale’ was in 1887.